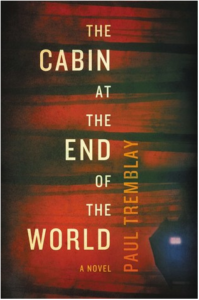

In contemporary popular literature which takes as its default Christianity as the dominant belief system, there are two main kinds of believer: the kind who want prayers answered and the kind who want to complain bitterly about how God could possibly let such-and-such happen. The two main protagonists of The Cabin At The End Of The World represent this dichotomy, despite both being shades of fairly tepid faith. Eric is the community Catholic dad who feels a bit guilty at not initiating his adopted daughter in the traditions that gave so much meaning to his life growing up, whereas his husband Andrew is firmly agnostic. The two have decided to take said 7 year-old daughter Wen on a summer vacation in the wilds of New Hampshire, in a remote cabin without cellphone service (which is already horror story enough for me.) As the book begins, Wen is out on the lawn collecting grasshoppers when she’s approached by a large man who introduces himself as Leonard, who turns out to be the harbinger of the world’s weirdest home invasion.

Leonard and the other three members of his cohort tell Wen’s parents that they had a vision of the end of the world that can only be averted if Wen’s family willingly sacrifices one of their own. Of course, neither Andrew nor Eric are convinced by this, and over the course of the next few increasingly bloody days, they must battle not only the home invaders but their own doubts and fears in order to survive… or, perhaps, in order to choose not to.

Leonard and the other three members of his cohort tell Wen’s parents that they had a vision of the end of the world that can only be averted if Wen’s family willingly sacrifices one of their own. Of course, neither Andrew nor Eric are convinced by this, and over the course of the next few increasingly bloody days, they must battle not only the home invaders but their own doubts and fears in order to survive… or, perhaps, in order to choose not to.

It’s an interesting idea with a bunch of symbolism that will delight cryptophiles like myself. Ultimately, tho, I had more fun investigating the “liner” notes than I had from reading the story, which just didn’t hang together as a novel for me. I wonder if this is due to my Muslim faith, that scoffs at the idea of prophetic revelation asking really big sacrifices of randos via randos. In most of the mainstream Abrahamic teachings, God sends the biggest tests to those of greatest faith (e.g. Abraham, Job) because the point is to see how strongly they believe. Demanding sacrifices of those who don’t strongly believe means nothing: how can you ask people who aren’t thoroughly invested in your message to choose to do or endure terrible things to prove their faith, when faith is already a thing of little reward to them?

Theology aside, Leonard and co are so bad at presenting their case that I can’t blame our heroes for doubting their message. I did not at any point believe that they actually heralded the end of the world, and put this squarely on the shoulders of Paul Tremblay for narrative choices that elided persuasive conversation in favor of hysterical confrontation (also, the bizarre two-person viewpoint chapters made me want to tear my hair out at the laxity of their entirely scattershot construction.) There was no convincing existential threat here beyond the crazy people with weapons, and no guarantee, barely even a promise, that the sacrifice of one of their family would save humanity. I thought that Andrew, neurotic and annoying as he was, and poor concussed Eric ultimately made the right choice, because faith isn’t just about fear and believing people who threaten brimstone and hellfire.

Despite the interesting premise, this was ultimately a wholly unconvincing execution that had me scratching my head at the high praise that led me to pick up this book in the first place. I was thinking of reading another book by Mr Tremblay in order to give this acclaimed author a fair shake, with the evocatively named A Head Full Of Ghosts looking the likeliest candidate, till a tart comment on that novel by a friend (hi, Cynthia!) made me discard the entire idea of reading more. Maybe it’s like my reaction to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road: some people love that shit, but I’d rather read something original, or at the very least, entertaining. Perhaps Mr Tremblay will write something that appeals in future. For now tho, there are so many amazing unread books out there that it seems like I’d be doing myself a disservice wasting time on books I’m already fairly confident I won’t enjoy.