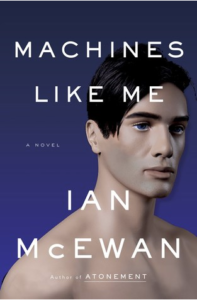

Come for the Alan Turing fanfic! Stay for the… um. Oh, dear. I knew going into this that it would be terrible, but I hadn’t realized exactly how terrible till I finished this utter nonsense of a 21st century novel.

Ordinarily, I like to just review a book without taking into consideration anything the author might have said outside of the work. If it can’t speak for itself, then it’s not as good as it ought to be, after all. In most cases, when I’m urged by a fan to read an author interview after I’ve excoriated the work, it’s because said interview is meant to answer questions the book does not, and somehow vindicate the lapse (note: it never does.) In this case, I’ll reference the much derided Guardian interview with Ian McEwan to explain why this novel is so bad, and how his words only confirmed what I suspected about his motives for writing such a flaccid piece of self-aggrandization. At first, I thought it was weird that the interview was less about Machines Like Me than it was about Mr McEwan himself, but then I realized it was of a piece with this miserable book, with their shared odd airs throughout of how lucky science fiction and technology and particularly the field of Artificial Intelligence were to have Britain’s Novelist turn his Discerning Eye to the subgenres.

Ordinarily, I like to just review a book without taking into consideration anything the author might have said outside of the work. If it can’t speak for itself, then it’s not as good as it ought to be, after all. In most cases, when I’m urged by a fan to read an author interview after I’ve excoriated the work, it’s because said interview is meant to answer questions the book does not, and somehow vindicate the lapse (note: it never does.) In this case, I’ll reference the much derided Guardian interview with Ian McEwan to explain why this novel is so bad, and how his words only confirmed what I suspected about his motives for writing such a flaccid piece of self-aggrandization. At first, I thought it was weird that the interview was less about Machines Like Me than it was about Mr McEwan himself, but then I realized it was of a piece with this miserable book, with their shared odd airs throughout of how lucky science fiction and technology and particularly the field of Artificial Intelligence were to have Britain’s Novelist turn his Discerning Eye to the subgenres.

Total bollocks, of course, because nothing in this book is a revelation to anyone with a working knowledge of sci-fi, which includes the millions of people who don’t even read the stuff but have watched, say, episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation, or a Terminator movie (the last one was hilarious, btw. Arnie still rules.) MLM is set in an alternate history 1980s Britain where Alan Turing never committed suicide and thus laid the foundations for technological marvels like cellphones and autonomously driven automobiles to be commonplace by the time the Falklands War/Invasion set off. The politics are mostly distracting and seem more like an excuse for Mr McEwan to get his digs in, deserved or otherwise, where he may; given how they make up so much of the book, it’s completely off-putting that they are then of little consequence to anything that happens in the narrative. And for all that this book slobbers over poor Mr Turing, who I agree died far too soon and in the most depressing of circumstances, it also makes him out to be an asshole. But maybe that’s just because he has to deal with our protagonist, the shiftless and clueless yet unceasingly superior Charlie Friend.

Charlie is a day trader with a chequered past. When he comes into a large inheritance, he impulsively decides to spend it on one of the 25 newly rolled out Adams and Eves: lifelike androids that are meant to be “companions” or somesuch nonsense (they’re all anatomically correct, so you can guess what they’ll actually be used for.) Since his Adam is meant to be programmed by him for personality traits, but since — in one of his few moments of self-awareness — Charlie doesn’t just want to make a clone of himself, he offers the opportunity to his upstairs neighbor, Miranda, to help him choose half of Adam’s personality, hoping it will draw him and Miranda closer, as he’s been in love with her for a while. Long story short, Adam falls in love with Miranda then winds up fucking everything up because of his “logic” circuits, then when Charlie tries to shut him down, Alan Turing gets mad.

What I can’t fathom is how a machine whose programming allows it to fall in love, that least rational of feelings, can also misunderstand justice and obligation as thoroughly as Adam does. No one can gainsay that there is a natural, if rough, justice to what Miranda did to Peter, so Adam’s insistence on following the letter of the law — when he with his alleged depth and breadth of learning in history and literature knows that the law is often unjust, and when everyone else is ready to put it all in the past — just seems like pedantic nonsense, especially given the book’s over-long ruminations on achieving ends in logic problems (we get it, Mr McEwan, you did your research. My undergraduate degree applauds you.) It’s also rubbish that he only returned the thirty quid to Charlie given that his upkeep cost far, far more than that, and you’d think he’d at least take that into consideration given how “broad” his “consciousness” was. Ugh, the entire thing was so insufferable. Mr McEwan plays fast and loose with logic in order to scaremong and draw false parallels. I’m sure he meant to be thought-provoking, but honestly this was just provoking nonsense.

Anyway, I put off reading it as long as I could because the reviews weren’t wrong, and I didn’t want to diminish my opinion of the author of one of the best books ever written, the chillingly brilliant Atonement. Granted, I thought Saturday, the only other book of his I’ve read, was over-hyped, tho I’ll acknowledged that when I first reviewed that novel, I was also far too generous with my praise of what, in retrospect, strikes me as banal. Perhaps a decade on, I will also revise my opinion of MLM, this time for the better, but given that it currently reads like second-rate genre trash from the 1970s — I mean, honestly there is nothing innovative about anything in this book and I am baffled by how disconnected its boosters must be from popular culture of the last forty years — I sincerely doubt it.