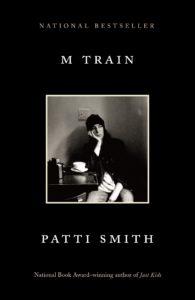

I loved Just Kids — it was one of my very favorite books of 2014 — so why didn’t M Train do much for me?

Smith gives a bit of a warning in the book’s very first line, “It’s not so easy writing about nothing.” (p. 3) The speaker is a cowpoke who is in a dream of Smith’s that she relates. They converse a bit more about writing and whose dream it actually is before she wanders out of the dusty café and wakes up. Is M Train really about nothing? An ornery cowpoke could surely make the case. After that first dream café, Smith visits many more cafés over the course of the book, and she drinks a lot of coffee. She relates mundane details of her life, notably including a tendency to lose material objects, when she feeds her cats, and dreams she has. She also goes on quite a bit about the detective shows she likes to watch on TV.

But Smith is enough of an artist that she can’t stick to the mundane. Despite considerable effort, she can’t make her life seem boring. Odd, distant, maybe even disconnected, but not boring, though at times I wondered how much she realized how different her life was from most people’s. Early in the book, she is catching up on her mail and discovers that one of the items that she has let sit idle for several weeks is an invitation to give a talk on a subject of her choice in Berlin at a meeting of a slightly eccentric club that she is a member of. She had been invited to join because she had wanted to photograph the boots of a particular Arctic explorer, whom the club commemorates. At the group’s 2007 meeting, in Reykjavik, she winds up having a clandestine midnight meeting with Bobby Fischer, at which they sing Buddy Holly songs until just before dawn. Late in the book, she decides she wants to visit Tokyo again, so she takes up what had been a standing invitation from her Japanese publisher. I suppose when you are the person Bob Dylan chooses to accept the Nobel Prize in his stead, you may view going to Tokyo on just a little more than a whim with the same equanimity as you do going to the corner café. Or perhaps the causality runs in the other direction. Who knows?

For a while, I thought that there were not many other people in this book, and that was its greatest different from Just Kids. Looking back again, I see that this is not quite true. There are a fair number of other people who pass through its pages, but that is mostly what they do: pass through, and at some emotional distance. The cowpoke recurs, the young man who makes excellent coffee at Smith’s favorite neighborhood café turns up several times, and a few others. Memories of her late husband appear quite a bit, from the odd journey that they took early in their marriage to French Guiana, to evenings spent in the boat that they kept in their front yard in Michigan until a storm felled a tree that crushed it. Fred is present to her very often, although he died a long time ago, when their children, who are becoming parents at the time of the book’s writing, were still young.

Still, my impression from this M Train is of Smith alone, generally in a room somewhere but sometimes occupying a table of her own in a café, drinking coffee and not writing. In Just Kids she was very close, and people were all around; in M Train she is at some remove, mostly by herself. Perhaps that is her statement on age.

A letter arrived. It was from the director of Casa Azul, home and resting place of Frida Kahlo, requesting I give a talk on the artist’s revolutionary life and work. In return I would be granted permission to photograph her belongings, the talismans of her life. Time to travel, to acquiesce to fate. For although I craved solitude, I decided I could not pass on an opportunity to speak in the same garden that I had longed to enter as a young girl. I would enter the house inhabited by Frida and Diego Rivera, and walk through rooms I had only seen in books. I would be back in Mexico. (pp. 110–11)

Acquiesce. It’s an inauspicious beginning for one of the book’s best passages, one in which Smith manages to connect with the people around her. She falls ill, and the women of the Casa Azul tend to her. Smith rallies just in time for her talk, which she improvised and closed with a song. The director of the museum was moved to tears, and all was well. Afterward, “I closed my eyes and saw a green train with an M in a circle; a faded green like the back of a praying mantis.” (p. 123)

After that episode, the crux of the book, there are more people and more connections, although the sense of distance never faded for me. She visits more places, buys a bungalow on Rockaway Beach shortly before the area is devastated by the storm Sandy. She has some final words with the cowpoke. Another year passes.