In 2015 Patricia Cowan has passed getting on in years and is definitely old. She’s reasonably well taken care of in the home where she lives now. She’s often confused, though, sometimes very confused, “VC” as it says in the notes the nurses and aides make. She’s not surprised, though; her mother struggled with dementia in her later years, too. She remembers her childhood well, the years during World War II that she spent at Oxford. And then.

It was when she thought of her children that she was most truly confused. Sometimes she knew with solid certainty that she had four children, and five more stillbirths: nine times giving birth in floods of blood and pain, and of those, four surviving. At other times she knew equally well that she had two children, both born by caesarian section late in her life after she had given up hope. Two children of her body, and another, a stepchild, dearest of them all. When any of them visited she knew them, knew how many of them there were, and the other knowledge felt like a dream. She couldn’t understand how she could be so muddled. If she saw Philip she knew that he was one of her three children, yet if she saw Cathy she knew she was one of her four children. She recognized them and felt that mother’s ache. (pp. 10–11)

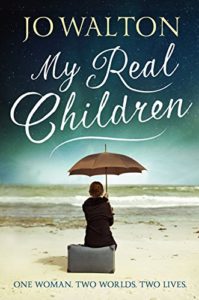

My Real Children tells the stories of those two lives. They start from the same childhood, the same wartime experiences and studies at Oxford. They share the same college boyfriend, the separation when she takes a teaching job after her degree while he goes on to finish, the letters that they exchange, letters that sustained her, letters that convinced her she was part of a great romance, letters that buoyed her as a young woman far from her fiancee, letters interrupted one day by a phone call. Mark, her intended, has gotten a very bad mark on his Oxford degree. The future of scholarship and philosophy that he had imagined is not to be.

“I won’t get a fellowship. I’ll have to become a schoolmaster. I’m calling to say I want to release you from our engagement now that I have no prospects.” Hysteria rose in his tones.

“But that’s ridiculous. I’ll stand by you, you know I will. I’ll wait as long as you like.”

“I won’t let you down, I promised to marry you, but you’ll have to marry me now or never!” Mark said.

Patty felt faint … She did not want to be a burden to Mark, to marry him when he could not afford to start a family. As a married woman she would not be permitted to teach, and what else did an English degree qualify her to do? Besides, if they married, she’d soon have a baby, and she’d be unable to work. Yet she couldn’t bear to give him up, to have his letters stop, for him to go out of her life.

“Oh Mark,” she said. “If it’s to be now or never then—”

The chapter ends. In the next chapter, she says “now” and in the one following “never!” That fulcrum levers Patty into two different worlds, one in which she is soon known as Tricia, marries Mark, does indeed start a family with him in short order, and in which all struggle with the strictures of the time that diminish his prospects and circumscribe hers even more tightly. In the timeline where she turns him down, she finds that without Mark’s letters, the school where Pat, as Patricia comes to be known, teaches is even more isolated and dreadful. Almost the sole ray of light is when a university friend invites her to come along on a trip to Italy during the summer break. “She replied to Marjorie and said she would go. … She could be miserable in Rome just as well as in Twickenham.” (p. 66) But of course she is not miserable. Pat begins a love affair that will last all of her life; she falls in love with Italy itself.

And so the two Patricias separate in 1949, grow to maturity, have families, survive heartbreak and trauma, live rich and full lives, and reunite, as it were, as a very confused patient in 2015. Neither of the worlds that Patricia knows is ours. It’s been a little while since I finished the book, and details of which events go in which timeline have faded, but the Soviets win the race to the moon in one of them. That may or may not be the one in which the superpower confrontation under JFK went down in history as the Cuban nuclear exchange (limited, fortunately; otherwise, one alternate history would have been much shorter than the other), and other tit-for-tat nuclear exchanges — between India and Pakistan, for instance — are a recurring part of international politics. Tricia’s timeline has more advanced space travel than Pat’s or ours; there’s a moon base, and academics spending a year there for research is routine by the 1990s. Pat’s has better biology, and a set of guidebooks to Italy by one P.A. Cowan.

Of Tricia’s four children who survive, the oldest is named Doug, which was fun for me. Although he has his own tragedies, which was of course less so.

In both worlds, Walton reflects on the burdens that women bear, and how so many systems work together to make them heavier. She writes of how larger currents of history ripple into the lives of ordinary people. My Real Children is not a fantasy of political agency; its characters do not shape the worlds that they live in, but they do contain those worlds and by showing them to readers, Walton invites reflection on life within more familiar constraints of gender, of class, of nationality, of background. Patricia’s stories are rich and well-told, two biographies equally real for readers, full of people with their own lives and tales. Now and never, forever and ever, in whichever world.