Rivers of London introduces Peter Grant, a young policeman in London who is just finishing up an undistinguished starting round of assignments when he is asked to stand guard at a pre-dawn murder site and things go, as they say, a bit sideways. “Sometimes I wonder whether, if I’d been the one that went for coffee and not Lesley May, my life would have been much less interesting and certainly much less dangerous. Could it have been anyone, or was it destiny? When I’m considering this I find it helpful to quote the wisdom of my father, who once told me, ‘Who knows why the fuck anything happens?'” (p. 3)

While Lesley is away from the scene, which, just by the by, was a beheading, a man tells Grant that he saw the whole thing. Grant asks him to give an official statement:

‘That would be a bit of a problem,’ said Nicholas, ‘seeing as I’m dead.’

I thought I hadn’t heard him correctly. ‘If you’re worried about your safety…’

‘I ain’t worried about anything any more, squire,’ said Nicholas. ‘On account of having been dead these last hundred and twenty years.’

‘If you’re dead, I said before I could stop myself, ‘how come we’re talking?’

‘You must have a touch of the sight,’ said Nicholas. ‘Some of the old Palladino.’ He looked at me closely. ‘Touch of that from your father, maybe? Dockman, was he, sailor, some such thing, he gave you that good curly hair and them lips?’

‘Can you prove you’re dead?’ I asked.

‘Whatever you say, squire,’ said Nicholas, and stepped forward into the light.

He was transparent, the way holograms in films are transparent. Three-dimensional, definitely really there and fucking transparent. I could see right through him to the white tent the forensic team had set up to protect the area around the body.

Right, I thought, just because you’ve gone mad doesn’t mean you should stop acting like a policeman. (pp. 6–7)

Nicholas describes what he saw, but then vanishes just before Lesley returns with the coffee. “‘Anything happen while I was away?’ she asked. I sipped my coffee. The words — I just talked to a ghost who saw the whole thing — utterly failed to pass my lips.” (p. 9)

A couple of days later, though, with a desk jockey role looming large in Peter’s future while Lesley is being taken on as a detective in the murder unit, those words do pass his lips when he is in conversation with someone else who has been spending hours observing the scene of the crime.

He was about one-eighty in height — that’s six foot in old money — and dressed in a beautiful tailored suit that emphasised the width of his shoulders and a trim waist. I thought early forties with long, finely boned features and brown hair cut into an old-fashioned side parting. It was hard to tell in the sodium light but I thought his eyes were grey. He carried a silver-topped cane and I knew without looking that his shoes were handmade. All he needed was a slightly ethnic younger boyfriend and I’d have had to call the cliché police.

When he strolled over to talk to me I thought he might be looking for that slightly ethnic boyfriend after all.

‘Hello,’ he said. He had a proper RP accent, like an English villain in a Hollywood movie. ‘What are you up to?’

I thought I’d try the truth. ‘I’m ghost-hunting,’ I said.

‘Interesting,’ he said. ‘Any particular ghost?’

‘Nicholas Wallpenny,’ I said.

‘What’s your name and address?’ he asked.

No Londoner ever answers that question unchallenged. ‘I beg your pardon?’

He reached into his jacket and pulled out his wallet.

‘Detective Chief Inspector Thomas Nightingale,’ he said, and showed me his warrant card.

‘Constable Peter Grant,’ I said.

‘From the Charing Cross nick?’

‘Yes sir.’

He gave me a strange smile.

‘Carry on, Constable,’ he said, and went strolling back up James Street. (pp. 28–29)

Reflecting on that conversation, that he told a senior Detective Chief Inspector that he was out looking for ghosts, Peter thinks that there may be worse things in his policing future than a desk job. What happens instead is that he is assigned to work with one Thomas Nightingale. Peter hurries to meet him in a Japanese restaurant near Covent Garden. After some preliminaries, Nightingale poses a question.

‘So, did he come back?’

‘No he didn’t,’ I said.

‘Ghosts are capricious,’ he said. ‘They don’t really make reliable witnesses.’

‘Are you telling me ghosts are real?’

Nightingale carefully wiped his lips with a napkin.

‘You’ve spoken to one,’ he said. ‘What do you think?’

‘I’m awaiting confirmation from a senior officer,’ I said.

He put the napkin down and picked up his teacup. ‘Ghosts are real,’ he took a sip. …

‘Is this where you tell me that there’s a secret branch of the Met whose task it is to tackle ghosts, ghouls, faeries, demons, witches and warlocks, elves and goblins…?’ I said. ‘You can stop me before I run out of supernatural creatures.’

‘You haven’t even scratched the surface,’ said Nightingale.

‘Aliens?’ I had to ask.

‘Not yet.’

‘And the secret branch of the Met?’

‘Just me, I’m afraid,’ he said.

‘And you want me to what … join?’

‘Help,’ said Nightingale, ‘with this inquiry.’

‘You think there’s something supernatural about the murder?’ I asked.

‘Why don’t you tell me what your witness had to say,’ he said, ‘and then we’ll see where it goes.’ (pp. 33–34)

And we’re off. Because of course there’s a supernatural aspect to the murder. The police — both ghost-believing and mundane — start out several steps behind and fall further back as things get worse, threatening to go not merely sideways but actually pear-shaped. Because one outlandish murder is not nearly enough. To make matters worse, there’s a simmering dispute between Mother Thames and Father Thames — two embodiments of the genius loci of the river — who do not get along well at all. (Mother Thames was a Nigerian nurse who came to the city in the 1950s. Father Thames has been around a lot longer, but he hasn’t been down from the countryside since the Great Stink of 1858.) If their conflict should escalate into a struggle to show who actually controls the river, that could go badly for the millions of mere mortals who live near its banks. And there are signs that some members of each Thames entourage would prefer conflict to the uneasy truce that has held for several decades.

Peter and Nightingale are there to sort it all out. Not everyone is keen on their involvement.

[Detective Chief Inspector Alexander Seawoll] was from Yorkshire, or somewhere like that, and like many Northerners with issues, he’d moved to London as a cheap alternative to psychotherapy. I knew him by reputation, and the reputation was, don’t fuck with him under any circumstances. He bore down the corridor towards us like a bull on steroids, and as he did I had to fight the urge to hide behind Nightingale.

‘This is my fucking investigation, Nightingale,’ said Seawoll. … ‘I don’t want any of your X-Files shit getting in the way of proper police work.’ (p. 39)

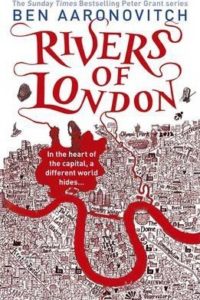

Three aspects made Rivers of London terrific fun to read. First, Aaronovitch is really funny, as the excerpts above show. He’s funny line by line (“Northerners with issues…”), in numerous different styles of dialogue — from the slightly flirty banter between Peter and Lesley through Nightingale’s drollery to many different sorts of understatement from the supporting cast — and on larger scales, as connections between incidents appear. Second, the book is such a love letter to London, and not some stuffily remembered Anglophile vision of crumpets and propriety, but real twenty-first century London of many layers, many nationalities, much noise and attitude, and the will to revel in all of that and more. Third, Aaronovitch balances the supernatural with the mundane, never letting one overwhelm the other. The secret part of the Met really is just Nightingale, and he’s not just hard-pressed because there is only one of him, he’s missing some things just because his perspective comes from a different era. He’s becoming more accomplished as a practitioner, at the price of being less savvy about modern technology and ideas. Peter has to sort him out sometimes too.

It’s a terrific, tense adventure. Things go from bad to worse, and only a desperate, dangerous plan has any chance of success. And that’s before the personifications of some of London’s lost rivers decide that they, too, should have a say in certain things.

At present there are eight more books in the main sequence of Peter Grant stories, plus numerous ancillary works. I’ve got a lot to look forward to.

Edit: Doreen’s review of the same book under its American title is here.

3 comments

4 pings

I love this series so hard! Did you hear that they’re making a TV show of it, from the production company started by Simon Pegg and Nick Frost? Also, check out my review of it from 2015; it was published in the US as Midnight Riot, and I can’t decide if that’s better or worse as a title.

https://www.thefrumiousconsortium.net/2015/09/14/midnight-riot-by-ben-aaronovitch/

Author

I did not know that about the TV show!

I’ve added a link to your review. I think I like the UK title better, mainly because readers get to meet several of the different rivers, and they’re important to the story.

I guess they thought Midnight Riot was more evocative for an American audience which might have thought the original a bit of pastoral ho-hum. I definitely prefer the original myself but I’m a wee bit of an Anglophile, and can see how MR was preferred from a marketing perspective.

[…] only three books into the Rivers of London series, and already they feel like comfort reading. I can feel […]

[…] asked Dominic. Thank god for aliens, I thought, muddying the waters since 1947. I’d once asked Nightingale the same question and he’d answered, “Not yet.” … “Not that I know about,” I […]

[…] was first introduced as someone who, like many Northerners with issues, had moved to London as a cheap alternative to […]

[…] Rivers of London was first published in 2011, the series has grown to nine novels, five novellas, and 12 graphic […]