I’ve been to this border before, though I’ve never been to the particular corner of Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece that Kapka Kassabova visits. “But the initial emotional impulse behind my journey was simple: I wanted to see the forbidden places of my childhood, the once-militarised border villages and towns, rivers and forests that had been out of bounds for two generations.” (p. xvii) She grew up in Bulgaria in what turned out to be the waning years of Communism, though nobody knew it at the time. Her family emigrated to New Zealand three years after the changes, just as she was beginning her university studies. While in New Zealand she published two collections of poetry; she moved to Scotland in 2005.

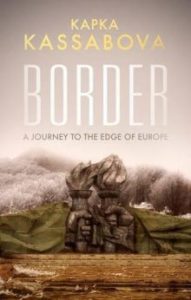

Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe was published in 2017 and tells of her travels on the Black Sea coast, in the plains of Thrace, and in the various mountain ranges that shape the borders among Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece. For Kassabova, the valleys and villages are often dark and mysterious places; she begins the book with what she describes as an uncanny experience, there are strange longings, the evil eye, old rituals still observed, death in the forest, and plenty of odd intimations. It’s an altogether different kind of journey in the Rhodope mountains than what Tim Moore enjoyed on the final legs of his bicycle ride along the length of the Iron Curtain. Moore’s was a late spring and early summer of increasing warmth and long uninterrupted stretches of good riding. It’s also quite different from what Patrick Leigh Fermor found in the later stages of his walk from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul. Of course three quarters of a century elapsed since Fermor’s visit, time enough for most of the horrors that Kassabova describes to have come and gone, but in The Broken Road the landscape itself seems different. Fermor’s is a land of sun and good company; Kassabova’s is one of dark woods, fog, caves and people who are often good company but nearly as often harbor worrisome secrets.

The casually cruel regime of A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka was close kin to the one in Bulgaria that shot so many people trying to leave Bulgaria for Turkey or Greece, the one that deliberately misprinted maps so that would-be escapees would think they had made it to safety when they were still on the unfree side of the Iron Curtain, the one that paid bounties to shepherds for leading defectors into the arms of the border guards. Who sometimes shot them then and there because it meant less paperwork than a capture and a trial and all that rigamarole.

Kassabova returns in part to reckon with that regime, to speak with people in the border region who had themselves been restricted in their movements even within Bulgaria. Parts of Border recall Stasiland by Anna Funder, a classic book about how the long shadow cast by a Communist regime and its secret services can outlast the regime itself by many, many years. (Kassabova acknowledges Funder’s book as useful in her research.) I read about a different part of Bulgaria’s reckoning in The Porcupine by Julian Barnes, which covers the trial of the unrepentant former Communist leader of a thinly-fictionalized Bulgaria.

Readers who are newer to the area or the themes will probably get more out of Border. It’s well written, the people and places are vividly described, and she captures lots of good detail. Since she’s a native speaker of Bulgarian and intimately familiar with the history and culture, if not the immediate area, she’s able to sift out nuances that might be lost on an outsider, able to be taken in by the people of the border villages as nearly one of their own. Those aspects give Border greater depth than the average travel book.

I think that Border draws on three visits that Kassabova made to the region, though she is never explicit about where one trip ends and another begins. She weaves the stories together as if they were all from one perambulation around the area, but then seasons and years change without her saying that she stayed there the whole time. The elision does not really affect the book’s overall arc, but I found it odd. At least some of her travel was in 2014 because she talks of seeing people from the Middle East in the woods, trying to make their way into the European Union, or further into it if they have gotten as far as Bulgaria. Writing later, she says that the summer she saw them their numbers had not yet swelled as they would the following year. The historical resonance of persecuted people trying to cross the border in the opposite direction of what Kassabova remembers from her youth is not lost on her.

In her visits to and around the border, Kassabova tells interesting stories of people who left, people who stayed, people who shot, people who died, people who practice the old ways, and people who are just getting by however they can. They’re often funny, and often melancholy, sometimes simultaneously. I hope she found what she was looking for.

1 ping

[…] Border, Kapka Kassabova traveled to the corner of Europe where Greece, Bulgaria and Turkey meet to find […]