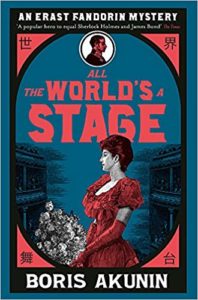

For a number of years, I was worried that Boris Akunin’s English-language publishers (the estimable Weidenfeld & Nicolson) had despaired of finding an audience for the Russian mystery writer’s work, and I would have to read the remaining stories in German and miss out on Andrew Bromfield’s witty translations, or really really really improve my Russian. In 2017, though, W&N returned publishing Akunin’s long-running series about Erast Fandorin, bringing out the eleventh book in the series, All The World’s a Stage. A twelfth, Black City, came out in 2018; two more novels, Planet Water and Not Saying Goodbye, as well as a collection of shorter tales, Jade Rosary Beads, await English translation.

All of which is to say that this deep in the series is probably not the best place to start. The Winter Queen, the first in the series, is probably not the best starting point either. I think that Akunin spent the first book figuring out what he was doing. The ones that come after, are more tightly plotted, better written, more vivid, and slyer. Turkish Gambit or Murder on the Leviathan are where I would start, if I were new to the series. They are also recognizable comments on established subgenres of mysteries, so readers unfamiliar with pre-revolutionary Russia will recognize the contours of the story, even if the settings, actions and modes of address are foreign.

Fandorin is the Russian Sherlock Holmes, with the benefit of a century of development in detective stories, so that the tales are not only interesting in and of themselves, but also for how Akunin addresses the conventions of the genre, and either follows them or subverts them. The author’s name is already a hint that he is going to play around with readers’ expectations. “Boris Akunin” is the nom de plume of Grigory Chkhartishvili (გრიგორი ჩხარტიშვილი, for the Georgian readers out there), and the surname roughly means “bad guy” in Japanese — Fandorin has extensive Japanese connections that are revealed over the course of the series. In Russian, names are often written with just the first initial and the surname; “B. Akunin” compresses to Bakunin, one of the best-known anarchist thinkers in the Russian tradition. Readers are thus forewarned that things are not as they seem.

Over the course of the previous books, Fandorin has risen through the ranks from a provincial policeman to a trusted state counsellor, and then fallen from grace. By the time All the World’s a Stage opens, however, “The times were long over when a quarrel with the authorities had obliged Fandorin to leave his native country and home city for many long years. Erast Petrovich’s personal foe had once been the most powerful man in the old capital, but now he (or rather, the little that remained of his most illustrious body) had long been reclining in a grandiose sepulchre, mourned but little by his fellow Muscovites. There was nothing to prevent Fandorin from spending as much time as he wished in Moscow.” (pp. 8–9)

The story begins in September 1911. Fandorin is in his early 50s, and at peace with himself. Masa, his Japanese manservant who is not only Fandorin’s foil but also his closest friend and associate for most of the last quarter century, also passed the half-century mark. Their tranquility is interrupted by the assassination of Pyotr Stolypin, the czar’s chief minister, and one of the few people thought capable of bringing enough reform to Russia to stave off revolutionary tendencies. Fandorin expects to be brought in as an independent expert to assist with the investigation, but two, three, four days pass with no call from the authorities. Finally, the phone rings, and in an uncharacteristically hasty exchange, Fandorin promises to do everything he can. Unfortunately, the person on the other end of the line was not a grandee from St Petersburg, but Chekhov’s widow, a long-time acquaintance of Fandorin’s, who has called seeking help in an entirely different case. Fandorin has given his word and cannot back out.

That call takes Fandorin into the world of Moscow theater, where Eliza Altairsky-Lointaine, a friend of the widow Chekhov, is terribly frightened of something, but will not say what a word about what it is. Fandorin makes his way to the theater that very night and has a perfect line of sight when a viper springs out of a post-show bouquet and nearly kills her on the spot. Well, that is one, as Fandorin would say. He acknowledges the universal truth that a theater in possession of an attempted murder or two must in want of a detective, and so he contrives to join the company, the better to be able to observe both suspects and potential victims.

Akunin also shows Fandorin in love for the first time since the initial volume in the series. The detective is very much surprised and confounded, and his state leads to a number of misunderstandings and misdirections that take the case in unexpected, but interesting, directions. He falls for Eliza, and she for him, but both pretend not to for their own reasons. On Eliza’s part, she is afraid that her ex-husband will try to kill Fandorin — if that’s a spoiler, someone should re-write the text on the dust jacket. Fandorin misreads Eliza’s distancing as disinterest, and wounded pride pulls him away. The injury is compounded when Masa is cast as the lead in the troupe’s next play, and Fandorin thinks that the two of them are falling for each other just as their characters the play do. But the play within the novel is key to finding the culprit; as all the masks fall away in the final act, Fandorin learns that Masa and Eliza have both been true, and is abashed.

With all of the twists and turns, I found All the World’s a Stage a little less focused than other Fandorin stories. The charm was still there, but I think that I would have enjoyed it more if there had been a bit less of it. I don’t know if Akunin thought the same, but Black City, next in the series, is noticeably shorter. I’m looking forward to seeing what Fandorin is up to in the Baku oil field, and whether he crosses paths with young Stalin. That is two. Or perhaps more accurately, twelve.

3 comments

Wait, so what was with his romantic shenanigans in The State Counsellor and The Coronation, then? I daresay he thought he was in love with both those ladies, too (with a gentlemanly separation of several years between them, of course.)

Author

Were there dalliances? Alas, my memory. I thought that his wife in The Winter Queen was his One True Love and that there would never be another. And I also think that he says in All the World’s a Stage that his heart had never been moved in that way for many year. Maybe I misinterpreted. Hm.

Well, there was the progressive young miss that he had to leave behind upon being exiled in TSC, and the whole business with the grand-duke’s daughter in TC nearly (?) a decade on, with the letter etc. I shall have to read the other books to properly compare and contrast, I suppose!