Steffen Möller’s second genial book about Poland and Germany takes the train ride from Berlin to Warsaw as his frame to share more anecdotes from a life lived in both countries. Möller’s engagement with Poland began more or less on a lark, when he signed up for a language seminar in Krakow in the mid-1990s. Not long after, he returned to teach German to unsuspecting young Poles. Some years later, and after publishing two books in Polish, he landed a role in the long-running soap opera “M jak Miłość,” (L like Love, which ended in December 2018 after 19 seasons and 1422 episodes). He played an immigrant potato farmer who can’t quite find a nice Polish girl to settle down with; the role made him a minor celebrity in Poland, possibly the best-known German who was neither a politician nor an athlete.

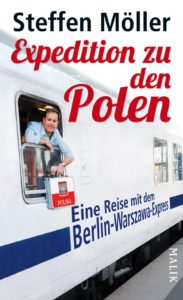

Expedition zu den Polen (the title translates literally as Expedition to the Poles, and carries the same pun on polar exploration in German that it does in English) was published in 2012, and Möller opens the book with a series of optimistic observations about Poland’s overall development, how it had weathered the 2008 financial crisis better than most European countries, and how his fellow Germans were largely missing the positive transformation of their neighbor of 40 million people. Möller contrasts Poland’s development with that of his home town, Wuppertal, somewhat tongue in cheek but nonetheless pointedly observing Wuppertal’s loss of population, shrinking public amenities, and general decline. I’ve been to Wuppertal a lot over the years, and it’s not as bad as all that, but the general point is valid: Wuppertal grew on nineteenth-century industry, the end of the twentieth was hard on it, and its path in the twenty-first has been uneven and uncertain.

The book really gets underway when he arrives at Berlin’s main train station for the 0637 Eurocity that runs to Warsaw East, via Berlin East, Frankfurt an der Oder, Rzepin, Swiebodzin, Poznan, Konin, and Warsaw Central. Each of these stops marks a chapter in the book, and for each chapter Möller also lists the distance, the travel time, a particular culture shock, and a Polish word or phrase appropriate to that leg of the trip. These range from “rajzefiber,” travel fever and an exact Polish transcription of the German word, to “super buty,” nice shoes, or “stara bieda,” literally “the old poverty,” but more metaphorically either “the old misery” or “same old, same old,” and according to Möller a common Polish answer to the question of how one is doing.

Möller is enough of a regular on the Berlin-Warsaw Express that he knows the conductors by name, and the Polish conductor on this train, Pan Mirek, becomes a regular character in Möller’s anecdotes from the trip. On the train, everyone has a reserved seat, but Möller spend most of his time in the dining car, where he strikes up conversations with various people as they pass the time there, or remains content to observe and listen to others. He tells his stories in short sections, seldom more than three or four pages and often less than two, so that the book glides by as swiftly and easily as the north European plain between the two capitals. They relate either incidents from one particular Berlin-to-Warsaw trip or more generalized observations about aspects of life in Poland, with a leavening of background about particular stops gleaned from other trips and stories from other parts of Poland. He’s not averse to the occasional, brief, infodump (a page and a half about Adam Michnik) or embedded listicle (matching Polish license tags with area of origin, or the canon of literature that Polish high school students should have read).

My favorite among the last was a list of the slang that has grown up among young Poles in Germany who “increasingly use German words in their mother tongue but then, funnily, conjugate and decline them very strictly according to Polish grammar.” He calls the mix “Dolski” a mash-up of the German and Polish words for their own languages, “Deutsch” and “Polski.” It’s probably only really funny if you have a passing acquaintance with both languages, which I do, so “Mam boka na piwo,” “zaszpeicherować” and “Telewizor jest kaputt” all tickled my funnybone.

He occasionally touches on more serious issues, such as the question of which name to use to refer to a place, especially places that were once part of Prussia or Germany. The unreflected use of the old German name can cause offense to contemporary Poles, and that opens the topic of all the different ways that people from a larger, wealthier, more powerful country can afford to be ignorant of the history and culture of their neighbors. Möller mostly keeps things light and funny, but the darker aspects of German-Polish relations are never completely absent.

He writes about many of the standards of living between two countries — holiday customs, office etiquette, mutual misunderstandings, romance, nonverbal communication — along with some particularly Polish aspects, such as the supposed near impossibility for non-natives to come to grips with the difference between perfect and imperfect verbs in the Polish language. He does this with a light touch, bringing warmth to his polar expedition, implicitly communicating to his German audience that Poland is interesting, safe, and on the upswing.

I took this very train last weekend, visiting Warsaw for the first time in about 20 years, and I was amazed at the changes in the city, though of course I should not have been. Still, it’s one thing to know in the abstract how Poland’s capital has gotten cleaner and wealthier, and quite another to breathe the air on streets no longer choked by old Skodas and Polski Fiats; to have a choice among dozens of fashionable restaurants and wine bars in a neighborhood where once the best option for lunch outside the newspaper office was the miniscule vietnamski kiosk; to see the facades in colors other than streaked gray; to pick up breakfast in a local bakery that clearly revels in the pan-European styles their bakers have mastered. Though perhaps this paean to contemporary Warsaw is better suited to another of Möller’s books.

Expedition zu den Polen is not perfect — there’s a strained bit in the middle about one-sided train romances — but it’s a pleasant and congenial companion for the trip from Germany to Poland and back. Möller’s not afraid to poke fun at himself, and he’s an enjoyable guide, ready with a quick, sympathetic laugh, or an anecdote that nicely illustrates a larger tendency.