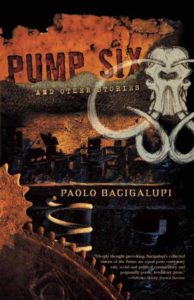

There’s a lot of ick in the ten tales that comprise Pump Six and Other Stories. Most of the settings are dystopias of one sort of another — mostly near-ish future, mostly Asian-inflected, mostly involving some sort of environmental collapse — and most of the characters in the stories are either horrible people in and of themselves, or wind up doing horrible things. Over time, I have read rather a lot about the history of Germany, Russia, and Central Europe, so I have more than a passing familiarity with how horrible people can be to each other; perhaps I should have just set the book aside as Not For Me and let it go at that.

The stories were originally published between 1998 and 2008; five of them first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, two in Asimov’s, and the rest elsewhere, except for the title story, which is original to the collection.

“The Calorie Man” and “Yellow Card Man” share a setting with Bacigalupi’s first novel The Windup Girl. In that world, natural crops have collapsed globally, and the only remaining crops that can provide sustenance are tightly controlled by multinational companies that effectively determine how many calories each person can have. The fossil-fuel economy has also fallen apart, and energy is provided by newfangled (and slightly handwavy) clockwork, sometimes wound by genetically recreated mammoths. It’s a striking setting, and probably a fun one to write about. “The Calorie Man” is also interesting for being set in the remains of the United States but told through the eyes of characters who escaped disaster in India and rebuilt their lives in New Orleans. I don’t think the setting works economically, but it’s probably not fair to poke quite so hard at a world that’s clearly devised as a warning.

“The Pasho” is, for me, the most interesting of the bunch. In its world, there is a long-running conflict between people from a dry, Central Asia–like region and an irrigation-based land of cities and gardens. The desert Jai are fierce fighters, proud of their adherence to tradition, but also poor thanks to the harshness of their lands and their relative technological backwardness. One of the Jai has gone down to the lush lands and acquired the learning of the Pasho, something like a technology and development priesthood. When he returns to his native village, his grandfather, a renowned raider in earlier years, questions whether he can still be Jai and dismisses him as unworthy. Bacigalupi shows the pride that other members of his family feel about the learning and status he has acquired, but his grandfather’s suspicion is shared by other villagers. The conflict is resolved with an interesting spin on softness and learning.

“Softer” is a straight-up horror story, I think, about a man who kills his wife and successfully flees his crime. The less said about it the better.

In “The People of Sand and Slag” all life is engineered to run on minerals and waste and whatnot. The apparently human protagonists, who are mercenary guards at a mine and as sociopathically violent as that job description suggests, discover a natural dog that has somehow survived in the mine’s environment. They are flummoxed about what to do with it, and find that “real” life is a lot more trouble than the kind of existence that they lead. Pretty soon the characters are weighing the costs of feeding the dog and keeping it healthy against the other things that they could do with the money, plus the novelty of maybe roasting it and finding out what natural meat tastes like.

“Pop Squad” is about killing children. The high-tech world of the story has perfected rejuvenation, making people functionally immortal, but the price is prohibiting reproduction. Some people do it anyway, and the lead character of the story enforces the prohibition by arresting the mothers (fathers are not on the scene in the incidents Bacigalupi chooses to show) and executing the children on the spot. Popping them. I had a very hard time reading this story, even though the main character does eventually start to have qualms about what he does. I am not sure why one writes a story like this, and I think that gets to my basic problem with the book, which is that many times it seemed to me that Bacigalupi came awfully close to glorifying, to revelling in the horribleness that he was depicting. Signs that I am not part of his intended audience, I suppose.

There’s less of that in Ship Breaker, his second novel, which I remember enjoying. I haven’t read any of his later works.

1 comments

I’m surprised you finished the book. I think I would have put it down and walked away. (Or maybe thrown it across the room?)