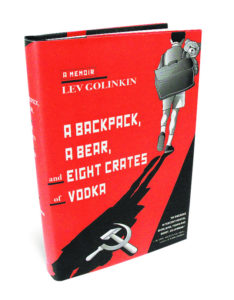

How did A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka turn out to be such an impossibly good book? I picked it up more or less on a whim during a visit to Texas — ok, memoir of leaving the Soviet Union as a kid and growing up in the States, could be interesting — and it sat unassumingly on my shelves for a couple of years. Now I know it was lying in wait to wallop me with a story that is by turns touching, harrowing and astonishing.

Lev Golinkin was born in 1980, in Kharkov, which was then part of the Ukrainian S.S.R., one of the fifteen union republics of the USSR. His early childhood memories recall for the reader how thoroughly rotten so much of the Soviet Union was, even under Gorbachev, even as Stalinist terror had receded to something less overwhelming but still capable of engendering random fear and harm. In Golinkin’s case, the harm is less random because his family is Jewish, and the casually violent anti-Semitism of the environment reaches even into the first grade. He is beaten by other boys for being Jewish, shit-stained toilet paper held in his face as other elementary school kids tell him that’s what he is for being a Jew. The teachers were studiedly indifferent.

The rot was there at the top, too:

On April 26, 1986, the year before I entered first grade, the Chernobyl nuclear plant (located less than three hundred miles from Kharkov) exploded, spewing a radioactive cloud over the Ukraine. Other, weaker countries would’ve had their citizens hunkering indoors and popping iodine tablets. But May 1 was International Workers’ Day, cancelling the parade was unthinkable, and so on we marched, blissfully unaware, soaking in the sunshine and the radiation. The reviewing stand was mostly vacant, of course, since local Party leaders had been alerted beforehand and had long evacuated the area, but the parade went off without a hitch. That’s commitment. (p. 7)

His father is an engineer, working on turbines across the Soviet Union. He is respected in his profession, with some patents to his name, but anti-Semitism affects him as well:

[H]e had spearheaded a paper that was selected for an international Communist expo in Bulgaria. A week before the trip, a low-ranking KGB sergeant showed up at Dad’s work with a letter from Dad to the expo committee. The letter explained that due to a recently broken leg, Dad would be unable to attend the exhibit and requested that the following [non-Jewish] coworkers represent the project instead of him. The only thing missing was Dad’s signature.

‘But my leg isn’t broken!’ Dad blurted out in a moment of idiocy (my father hated lying).

‘Would it help if it were?’

Dad hastily scribbled his name, went for a walk, and returned the next day, ready to work. (p. 25)

His sister, twelve years older, was on track to earn a gold medal for straight A’s in high school, which would qualify her for professions such as medicine. The school director called Golinkin’s father in for a conference:

‘Comrade Golinkin, your daughter is a fine student and a very nice girl. I asked you here because I admire her, and I don’t want this to take her by surprise. She will get a B, and only one B, which will preclude her from getting the medal; it’s the best I can do for her. I have my orders, just like everyone else.’

Dad was confused. Un-affirmative action policies of the Soviet Union shifted and varied depending on the year, the republic, and the whim of the dictatorship. Some years, certain ethnicities would be tolerated in certain professions and institutions; then, a nameless bastard in the nameless echelons of the bureaucracy would decide that too many zhidi were getting straight A’s, and a memo would be generated and sent out. Dad knew all this; what confused him was why the director bothered to bring him in to discuss it.

‘Of course, we do live in an open society, and you do have the option of filing a complaint with the administration. I know that Lina can be … tenacious, and may urge you to follow this course of action. But I must strongly advise you against it.’ The director leaned forward. ‘The teachers will then have to justify your daughter’s not qualifying for the medal, and instead of a single B she will have to start receiving Cs and Ds. I don’t want that to happen; I don’t want her to be any more upset than necessary. I’m trying to help you. Do you understand?’ (pp. 23–24)

This is the world that Golinkin is growing up in, a world where his best friend from early childhood, with whom he had played countless rounds of Germans and Soviets, discovers he’s Jewish and never speaks to him again. Petty exercises of arbitrary power are everywhere, and even well into the years of glasnost and perestroika, there’s fear.

The five men in red armbands stroll through the apartment block. They have the businesslike gait of wolves near caribou, purposeful but not hurried; there’s always someone weak, injured, unlucky, and the pack will have its dinner. Wherever the men are headed, there’s no need for improper haste. They’re not KGB; you don’t see those until they come for you in the middle of the night, and nobody hears about it until the next morning. … They’re druzhinniki, neighborhood watchmen assigned to patrol for drunks and loiterers, but on their arms is the plain red band, the crimson banner of the USSR, and with it comes all the malice and paranoia and fear that the color has ingrained into my head. …

I don’t know why I am afraid of the men. I don’t remember learning to be afraid of them, the police, anyone in the government. No one taught me that the [tsarist] Nikolai coins are dangerous or that certain words like ‘synagogue’ are not to be uttered except in the apartment, but I know it, as surely as I know a hot stove will burn my hand and scissors are not to be played with. Whisk whisk, whisk whisk, the armbands rustle against the men’s coats as their arms swing on the walk. Keep walking, don’t stop, not here, don’t stop pounds in my head. Mitya the yard keeper has developed a keen interest in corralling every dirty snow patch onto the sidewalk around him, and he concentrates on the slush, his pipe forgotten. … Whisk whisk, don’t stop / whisk whisk, don’t stop, goes the cadence. Kolya stares at a balcony and I stare at the coins, but the babushki stare at the druzhinniki. No babushka—Russian or Jewish—ever looks away. Something happens to a woman once she gets old enough to be called a babushka. Lina told me something about their surviving the evacuation and the war and the things before the war that no one talks about, times when people disappeared on a regular basis and the black cars were an everyday thing. ‘They stare because they’re alive,’ said Lina, but I’m not quite sure what she meant. Whisk whisk, whisk whisk through the yard, and stolid scarf-wrapped heads swivel on benches to keep the men in sight.” (pp. 41–43)

And then in late 1989, the geopolitical stars align. Western pressure has led the Soviet leadership to allow large numbers of Jews to leave, bound for Israel or for the West. The American Congress has opened immigration to many thousands of Soviet Jews. Suddenly, the Golinkins are on their way out. No more beatings for Lev, no more humiliations for his father or sister, no more KGB requests for his mother, a psychiatrist, to sign papers allowing the institutionalization of people protesting against the system. The exit is as uncertain as anything related to Soviet bureaucracy, and they hear that permission from the West will expire at the end of 1989. Their last encounters with Soviet border guards are as frightening as any harassment by the state up to that point, and there are so many ways that at the last moment they could have been prevented from exiting.

But exit they do, and find themselves among hundreds at Vienna’s Westbahnhof, which as far as their information had reached. “Get to Westbahnhof, people will take care of you.” What they discover at the train station is a system that had been set up to accommodate dozens suddenly having to cope with hundreds of new arrivals every day, and creaking badly under the strain. They are refugees, caught up in the machinery of processing people who have left one home with no clear idea of what might come next.

There is the hotel in lower Austria where dozens of families are parked while the responsible committees figure out how to get them to the centers that had been properly set up for refugees, and onward to the accepting countries. The hotel, Golinkin learned much later, was run by someone who had refugees in his own family background, and who remembered. There is Peter the forester, who owns a military-grade Mercedes jeep and has the means to buy the best items the refugees had brought out with them, particularly fine rugs. Peter takes on Golinkin’s father as a translator, and eventually arranges for him to do work as an engineer for a firm in Vienna. Considering the border guards had burned all of the family’s documents, including professional qualifications, the work in Vienna gave Golinkin’s father a huge step up in finding proper employment once the family reached America.

Second, migrants with no relatives in America were likely to be placed by HIAS into an urban Jewish community … Cities have dense concentrations of low-level, immigrant-ready jobs coupled with public transportation, Laundromats, pharmacies, grocery stores, and other conveniences of Western life squeezed into a few blocks … The whole idea was to ease the lonely transition to America by plugging isolated refugees into long-established linguistic, ethnic, and immigrant networks.

Problem is, the story of my family flies in the face of both. Every one of the fifty families stationed in Binder’s hotel had been transferred to Rome, save us. We were moved to Vienna … And then there’s West Lafayette—even with the entire student body of Purdue University [where a kindly administrator persuaded the engineering faculty to take on Golinkin’s sister as a fully funded doctoral candidate] thrown in, the town still comes up a few million short of a metropolis. The Russian enclave of Tippecanoe County had consisted of us and one other family adopted by the community.

Why were we kept in Austria for six months? How did we wind up in Indiana? Time rolled by, my family met other refugees, heard other stories, and the more we shared, the more our story stood out, and still the answers lay hidden, obscured by years and by a transformed world. For many years, I didn’t think about any of this—in fact, I did everything I could to ignore, omit, and otherwise bury memories of our journey and of the Soviet Union—but in 2006, as an adult seeking to understand my past, I set out to discover what happened. (pp. 223–24)

And that became this astonishingly good book.