Here is Ursula K. Le Guin on life in pre-Roe America:

My friends at NARAL asked me to tell you what it was like before Roe vs. Wade. They asked me to tell you what it was like to be twenty and pregnant in 1950 and when you tell your boyfriend you’re pregnant, he tells you about a friend of his in the army whose girl told him she was pregnant, so he got all his buddies to come and say, “We all fucked her, so who knows who the father is?” And he laughs at the good joke.

They asked me to tell you what it was like to be a pregnant girl — we weren’t women then — a pregnant college girl who, if her college found out she was pregnant, would expel her, there and then, without plea or recourse. What it was like, if you were planning to go to graduate school and get a degree and earn a living so you could support yourself and do the work you loved — what it was like to be a senior at Radcliffe and pregnant and if you bore this child, this child which the law demanded you bear and would then call “unlawful,” “illegitimate,” this child whose father denied it, this child which would take from you your capacity to support yourself and do the work you knew it was your gift and your responsibility to do: What was it like? (p. 7)

Here is Ursula K. Le Guin on writing and business:

Right now [November 2014], we need writers who know the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art. Developing written material to suit sales strategies in order to maximise corporate profit and advertising revenue is not the same as responsible book publishing or authorship.

Yet I see sales departments given control over editorial. I see my own publishers, in a silly panic of ignorance and greed, charging public libraries for an e-book six or seven times more than they charge customers. We just saw a profiteer try to punish a publisher for disobedience, and writers threatened by corporate fatwa. And I see a lot of us, the producers, who write the books and make the books, accepting this — letting commodity profiteers sell us like deodorant, and tell us what to publish, what to write.

Books aren’t just commodities; the profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art. We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words. (pp. 113–14)

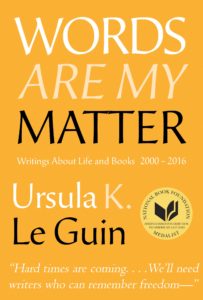

Not every essay in Words Are My Matter is as trenchant (nor, to be honest, is every one as good), but the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and many of the parts are very good indeed. Le Guin divides the book into three sections. The first, from which the two excerpts above are drawn, is “Talks, Essays, and Occasional Pieces.” Many of them were written on commission, or for a specific event, but one of the best, “Living in a Work of Art,” was written to discover what she thought about a particular subject: her childhood home, which was built by Bernard Maybeck, a well-known architect of the first half of the 20th century. Discussing that essay in her introduction to the book, she discloses one thing she thinks about writing well. “When I can use prose as I do in writing stories as a direct means or form of thinking, not as a way of saying something I know or believe, not as a vehicle for a message, but as an exploration, a voyage of discovery resulting in something I dind’t know before I wrote it, then I feel that I am using it properly.” (p. iii)

In the second section, “Book Introductions and Notes on Writers,” she discusses a dozen writers, sometimes limiting her thoughts to one book but more often ranging through the writers’ works and biographies, noting themes and obsessions, relations among their works and to wider streams in history and literature. Some of the writers were completely new to me, H.L. Davis, for example, whose Honey in the Horn Le Guin discusses as a book that has fallen out of favor and depicting a world of rural Oregon in the early 1900s that’s nearly completely gone a century later. Others, such as Philip K. Dick or H.G. Wells (who is the subject of three essays in this section), I know reasonably well, and it’s interesting to compare my recollections with what Le Guin sees in each of them. Best of all, though, is her long and enthusiastic essay on a Nobel winner from Portugal, “Examples of Dignity: Thoughts on the Work of José Saramago.” She praises “His extraordinary gifts of invention and narration, his radical intelligence, wit, humor, good sense, and goodness of heart, [which] will shine out to anyone who values such qualities in an artist.” (155) Further, “He has seen most of the twentieth century, and has had time to think about it, decide what matters, and learn how to say it. The energy and mastery with which he says it is a marvel. He is the only novelist of my generation who tells me what I didn’t know, or rather, what I didn’t know I knew: the only one I still learn from.” (p. 155) Le Guin also offers an interesting summary of H.G. Wells’ understanding of life “as evolution: necessary and unceasing change. What stays fixed dies. What adapts goes on. The more flexibly it adapts, the farther it goes. Openness is all. Change can be brainless and brutal or intelligent and constructive. Morality enters the system only with the thinking, choosing mind. Wells imagined both dark and bright futures because his creed allowed both while promising neither, and because the eighty years of his life were years of immense intellectual and technological accomplishment and appalling violence and destruction.” (p. 185)

“Book Reviews,” the third section, offers about three dozen reviews, with authors from Margaret Atwood to Stefan Zweig. “It’s an interesting and demanding form. And one can say a good deal in a review that has to do with wider matters, literary and otherwise.” (p. ii) Indeed. There’s more on Saramago, which is terrific, and an introduction to another great writer I knew nothing about — Sylvia Townsend Warner. “I had the great good fortune to be introduced to Sylvia Townsend Warner late in her life, in her damp, tobacco-smoke-varnished Naiad of a house, which was in Maiden Newton, on the river Frome, and also, from time to time when the river flooded, in it. She was very old, very tired, very kind.” (p. 289) The review is ostensibly about Dorset Stories, but Le Guin seems to prefer another book by Townsend Warner. “The very late stories about elves, collected as Kingdoms of Elfin, are among the strangest of her works; there is a lordly, icy, anguished indifference in them that chills the blood. Critics who confuse fantasy with whimsy and believe that only realism can deal with pain and cruelty should be exposed to Townsend Warner. She can cast a cold eye with the best of them.” (p. 289)

Words Are My Matter concludes with a journal, or at least parts of one, that Le Guin kept while at a week-long writing retreat in 1994. I found it more of a coda or an appendix, but I also think that I was not much a part of her intended audience. I did like a section where she gives a piece of her mind about various snobberies:

[Clifford] Geertz is ineffably Ivyleague, a pity; it makes him smart-alecky sometimes, and though he is quite right to point out the curious reversal of fortune in so many academic careers, from the Big School as a graduate student to the Little School for the career, his assumption that Princeton is Paradise is appalling in an anthropologist. I was ashamed to read it. Those people really do believe in the hierarchy of intelligence and merit — I guess they have to? Of course better scholars are likely to come from the centers of scholarship than from the outskirts, it’s a matter of critical mass; but the preening, the snobbery, the prejudice, and the absolute indifference to the fact that, aside from specialised scholarship by wealth, there is no difference in the students at all: that’s unforgivable in an educated mind. (pp. 312–13)

I finished reading Words Are My Matter months ago, and have found myself dipping back into it from time to time to look at something anew, or to reconsider what Le Guin said on one subject or another. Writing about it today, I have had to work hard not to settle in again and re-read large swathes of the book. What more could I ask of a collection of essays?

(Words Are My Matter won the 2017 Hugo for Best Related Work. I was a Hugo voter that year and placed it first on my ballot.)