You know what would be really scary? A novel written from the point of view of one of the women who believed wholeheartedly in the tenets of the Republic of Gilead, who rejoiced in the work they were doing, who revelled in her role as helpmeet, as implementer of God’s will on an earth that is fallen but that can, with hard work and stern discipline, come just a little bit closer to redemption. Because there would be such women. Scarier still would be the number of people who would take up the book and see the narrator as an upstanding example of Christian womanhood.

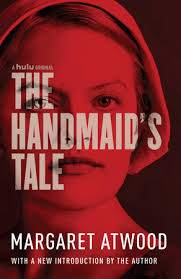

The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood’s 1984 novel, posits an America transformed into a repressive theocracy, rapidly remade into a new society by the combination of long preparation and a bloody precipitating incident. As she writes in her February 2017 introduction to the current edition, “Having been born in 1939 and come to consciousness during World War II, I knew that established orders could vanish overnight. Change could also be as fast as lightning. It can’t happen here could not be depended on: anything could happen anywhere, given the circumstances.” (IX) I’ve lived in a country that was invaded by a neighbor’s army. One afternoon we were watching our kids dance and sing at the school’s end-of-summer-term program, the next afternoon it was impossible to get to the western half of the country because the road and railroad bridges had been bombed and fallen into the river they spanned. Fourteen hours later, because we were very, very privileged, we evacuated across a peaceful border, having told our small children that we were going on vacation.

Gilead is a plausible American theocracy for another reason. “One of my rules was that I would not put any events into the book that had not already happened in what James Joyce called the ‘nightmare’ of history, nor any technology not already available.” (X) It owes a bit to Iran after the 1979 revolution, a bit to the Puritan polities of early America, and plenty to the expressed desires of 1980s conservative Christians.

Atwood tinkers with the background a little bit to produce the setting she wants to write about and the story she wants to tell. There are multiple wars, somewhere; she implies that at least some nuclear strikes have been involved. Gilead has Colonies, where dissidents and expendables can be sent, a sort of external gulag. The book’s characters never hear much about the Colonies, so they can retain the vagueness they need to work.

Chilling as the main narrative is, genocide is taking place off-stage. The characters of The Handmaid’s Tale live in a tightly constrained world. Even so, a little news filters through, and one of the things that is briefly mentioned is the emptying of cities such as Detroit whose populations — by implication mostly African-American — are being transported to new, unspecified homelands. Whether the model Gilead is following is the Khmer Rouge or Nazi Germany is immaterial, there is mass slaughter happening somewhere.

With that, Atwood shows readers how someone living in a totalitarian system might well not have known about the full extent of the atrocities the people of the system are committing. Media are state-controlled, and untrustworthy. They are at any rate strictly circumscribed. Women are not supposed to read, and their conversation is both limited by ritual and prone to betrayal. Rumors spread, but they are indistinct.

The things that the first-person narrator, Offred, witnesses are terrible enough. She sees executions, she sees the bodies of people put to death by the state hung on hooks on a wall as examples for the rest of the population. In the early years of Gilead, she attempted to escape with her husband and their child. They were betrayed at the border. She ran. He ran. She escaped, but she does not know his fate. She heard gunfire; sometimes she thinks he is alive, sometimes not. The state took their child.

The Handmaid’s Tale is not a story of resistance and rebellion. Offred would like to resist, would like to escape, but the system is far stronger than she is. Suicide is one means of escape; arrest more likely still. Gilead has that in common with historical totalitarianisms. It is all too easy to become dead, and that is far and away the most probable fate for resisters. Instead, Offred takes whatever small victories she can find. The existence of the Tale can itself be counted as a victory. There were few gulag diaries to begin with, and fewer still survived.

Atwood even gets the tawdry corruption that lurks in every dictatorship. Gilead is the embodiment of God’s plan on earth, but that only goes so far. Some of the powerful men are themselves above the rules, and Offred sees them engaging in almost all of the proscribed vices. Further down the ranks, it’s difficult to see where resistance ends and corruption begins, but Offred also witnesses slips minor and major. Maybe it’s people humanizing an inhuman system, maybe it’s people playing for momentary advantages, maybe it’s people using whatever power they can scrape together, underpinned by the threat of ratting someone out to the authorities. In communism, in Nazism, in countless petty tyrannies it has been all of these; Gilead is no exception.

The Handmaid’s Tale is also specifically a story of patriarchal oppression. Gilead is set up to benefit men, and men at the top of the hierarchy more than others. One of the first acts of the dictatorship is to deprive women of jobs and money. Made chattel, they are then categorized into Wives (for high-status men), Econowives (a cheaper model), Marthas (unmarried house servants), Aunts (female enforcers of the social order), and Handmaids (who provide children, if the Wives do not). Offred is one of the latter, and if she does not breed true within a certain amount of time, she will be sent to the Colonies to be worked to death. Offred remembers the time before, and one of her moments of deepest despair is when she realizes how many men she knew liked the new system, even if they themselves do not hold high rank in the new order.

Nearly 35 years after its first publication, The Handmaid’s Tale is a classic, chilling dystopian vision. It’s a warning about how much can change so fast, about how unbridled power makes itself felt, and about how strong such systems can be.