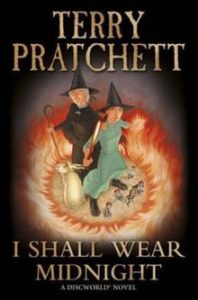

Late Discworld offers at least one great book before the end: I Shall Wear Midnight, the fourth Tiffany Aching novel. In contrast to all of the Discworld books aimed at adults from Monstrous Regiment onward (with the possible exception of Thud!), the story and conflicts in the Tiffany Aching stories arise from the characters themselves rather than from some element that Pratchett has decided in advance to examine within the framework of life on the Disc. By her fourth book, Tiffany has grown enough so that the precociousness the story requires is not as much at odds with the age that she is supposed to be within the story.

As I Shall Wear Midnight opens, Tiffany is a teenager doing something very typically teen: thinking that everyone is watching her and wondering about what she is doing. Only in her case they actually are, because she is the only witch in all of the Chalk. People see what she does because witches naturally stand out, and they pay extra attention because she is the only one they know. It’s a balance of awkward and self-assured that Pratchett captures perfectly, with an added dash of the absurd because Discworld is a fantastic farce at heart.

When you were a witch, you were all witches, thought Tiffany Aching as she walked through the crowds, pulling her broomstick after her on the end of a length of string. It floated a few feet above the ground. She was getting a bit bothered about that. It seemed to work quite well, but nevertheless, since all around the fair were small children dragging balloons, also on the end of a piece of string, she couldn’t help thinking that it made her look more than a little bit silly, and something that made one witch look silly made all witches look silly.

On the other hand, if you tied it to a hedge somewhere, there was bound to be some kid who would untie the string and get on the stick for a dare, in which case most likely he would go straight up all the way to the top of the atmosphere where the air froze, and while she could in theory call the stick back, mothers got very touchy about having to thaw out their children on a bright late-summer day. That would not look good. People would talk. People always talked about witches. (pp. 2–3)

There’s the awkwardness and also one of the key themes of the book: how witches fit in with the communities where they live, and the uneasiness all around that, especially in a place like the Chalk, which had been known to burn witches in the past and only accepted Tiffany because she was so emphatically one of them. Amidst a seemingly jocular description of the scouring fair of the Chalk — a three-day event where the people of the Chalk come together for feasting, games, and scouring the outline of the giant so that the white chalk that formed him (“and he was quite definitely a he, there was no possible doubt about that” p. 5) was free of any grass that might have grown over it in the course of the year — Pratchett strews clues of how the story is going to develop and what it will involve.

[Nanny Ogg] was generally thought of as a jolly old soul, but there was a lot more to the old woman. She had never been Tiffany’s teacher officially, but Tiffany couldn’t help learning things from Nanny Ogg. She smiled to herself when she thought that. Nanny knew all the old, dark stuff — old magic, magic that didn’t need witches, magic that was built into people and the landscape. It concerned things like death, and marriage, and betrothals. And promises that were promises even if there was no one to hear them. And all those things that make people touch wood and never, ever walk under a black cat. …

And she had told Tiffany about the old days, when it seemed that witches had a bit more fun. The things that you did around the changing of the seasons, for example; all the customs that were now dead except in folk memory which, Nanny Ogg said, is deep and dark and breathing and never fades. Little rituals.

Tiffany especially liked the one about the fire. Tiffany liked fire. It was her favourite element. It was considered so powerful, and so scary to the powers of darkness, that people would even get married by jumping over a fire together. Apparently it helped if you said a little chant, according to Nanny Ogg, who lost no time in telling Tiffany the words, which stuck immediately in Tiffany’s mind; a lot of what Nanny Ogg told you tended to be sticky.

But those were times gone by. Everybody was more respectable now, apart from Nanny Ogg and the giant. (pp. 6–8)

Having just remembered her deep connections, Tiffany feels as alone and self-conscious as any other teen.

Alone in the crowd, Tiffany sighed. It was hard, when you wore the black, pointy hat. Because, like it or not, the witch was the pointy hat, and the pointy hat was the witch. It made people careful about you. They would be respectful, oh yes, and often a little bit nervous, as if they expected to look inside their heads, which as a matter of fact you could probably do … But these weren’t really magic. Anyone could learn them if they had a lick of sense, but sometimes even a lick is hard to find. People are often so busy living that they never stopped to wonder why. Witches did, and that meant them being needed: oh yes, needed — needed practically all the time, but not, in a very polite and definitely unspoken way, not exactly wanted. (p. 11)

Tiffany is not only alone, she is in a place where people were not really used to witches, where within Tiffany’s lifetime they had been downright hostile. She is making progress, but it’s yet another burden on her young shoulders.

And it was working. The storybook pictures of the drooling hag were being wiped away, every time Tiffany helped a young mother with her first baby, or smoothed an old man’s path to his grave. Nevertheless, old stories, old rumours and old picture books still seemed to have their own hold on the memory of the world. (p. 12)

The old stories and old ways that Nanny Ogg knows did not all work in favor of the witches. Right after Tiffany has that thought, two younger girls bring her a bouquet that might show their enthusiasm, or might have a secret message that they don’t think much of her; they ask similarly double-edged questions about what it’s like to be a witch and whether or not Tiffany has a beau. The chapter concludes with some comic business about the rolling of the cheese, but the next one shows another side of traditional life in the Chalk.

“No one controls the [rough] music, Mr Petty, you know that. It just turns up when people have had enough. No one knows where it starts. People look around, and catch one another’s eye, and give each other a little nod, and other people see this. Other people catch their eyes and so, very slowly, the music starts and somebody picks up a spoon and bangs it on a plate, and then somebody else bangs a jug on the table and boots start to stamp on the floor, louder and louder. It is the sound of anger. It is the sound of people who have had enough. Do you want to face the music?” (p. 30)

Mr Petty deserves the rough music, and deserves what Tiffany does to him with pain that he has inflicted on others, and yet people in the village have also known Mr Petty all his life, and remember when he was more or less a good sort. They remember when the Chalk didn’t countenance witches, too, and somewhere in the collective there are fears of someone with the kind of power that Tiffany can muster. Fears that can lead to action.

The diffuse fears and jealousies find a focal point, egged on by something sinister and non-corporeal, and the main plot of I Shall Wear Midnight is underway. It’s a good one, tightly constructed and tense but leavened with levity courtesy of the Mac Nac Feegles, but the real pleasure of the book is seeing the characters being themselves and reveling in their humanity. There is, for example, a brilliant scene with Tiffany and the Baron of the Chalk, who is dying. She helps ease his pain, and they have an open dialogue that touches on many different, important things.

“Thank you, Miss Tiffany Aching. And now, I would like to sit in my chair.”

This was unusual, and Tiffany had to think about it. “Are you sure, sir? You are still very weak.”

“Yes, everybody tells me that,” said the Baron, waving a hand. “I can’t imagine why they think I don’t know. Help me up, Miss Tiffany Aching, for I must speak to you.” …

“I dreamed I had a visitor here last night,” said the Baron, giving her a wicked little grin. “What do you think of that then, Miss Tiffany Aching?”

“At the moment I have no idea, sir,” said Tiffany …

“It was your grandmother, Miss Tiffany Aching. She was a fine woman, and extremely handsome. Oh yes. I was rather upset when she married your grandfather, but I suppose it was for the best. I miss her, you know.”

“You do?” said Tiffany.

The old man smiled. “After my dear wife passed on, she was the only person left who would dare to argue with me. A man of power and responsibility nevertheless needs somebody to tell him when he is being a bloody fool. Granny Aching fulfilled that task with commendable enthusiasm, I must say. It is my hope, Miss Tiffany Aching, that when I am in my grave you will perform the same service to my son Roland who, as you know, is inclined to be a bit too full of himself at times. He will need somebody to kick him up the arse, metaphorically speaking, or indeed in real life if he gets altogether too snotty.”

Tiffany tried to hide a smile, then took a moment to adjust the spin of the ball of pain as it hovered companionably by her shoulder. “Thank you for your trust in me, sir. I shall do my best.” …

“Very good. Incidentally, Miss Tiffany Aching, I cannot conceal my interest in the fact that you do not curtsy in my presence these days. Why not?”

“I am a witch now, sir. We don’t do that sort of thing.”

“But I am your baron, young lady.”

“Yes. And I am your witch.”

“But I have soldiers out there who will come running if I call. And I am sure you know, too, that people around here do not always respect witches.”

“Yes, sir. I know that, sir. And I am your witch.” …

“Then you are your own person, Miss Tiffany Aching?”

“I don’t know about that, sir. Just lately I feel as if I belong to everybody.”

“Hah,” said the Baron. “You work very hard and conscientiously, I’m told.”

“I am a witch.”

“Yes,” said the Baron. “So you have said, clearly and consistently and with some considerable repetition. … It is true then, is it?” he said. “That some seven years ago you took an iron skillet and went into some sort of fairyland, where you rescued my son from the Queen of the Elves — a most objectionable woman, I have been given to understand?”

Tiffany hesitated about this. “Do you want it to be so?”

The Baron chuckled and pointed a skinny finger at her. “Do I want it to be? Indeed! A good question, Miss Tiffany Aching, who is a witch. Let me think … let us say … I want to know the truth.”

“Well, the bit about the frying pan is true, I must admit, and well, Roland had been pretty well knocked about so I, well, had to take charge. A bit”

“A … bit?” said the old man, smiling.

“Not an unreasonably large bit,” said Tiffany quickly.

“And why didn’t anybody tell me this at the time, pray?” said the Baron.

“Because you are the Baron,” said Tiffany simply, “and boys with swords rescue girls. That’s how the stories go. That’s how stories work. No one really wanted to think the other way round.”

“Didn’t you mind?” He wasn’t taking his eyes off her, and he hardly seemed to blink. There was no point in lying.

“Yes,” she said. “A bit.”

“Was it a reasonably large bit?”

“I would say so, yes. But then I went off to learn to be a witch, and it didn’t seem to matter any more. That’s the truth of it, sir. Excuse me, sir, who told you this?”

“Your father,” said the Baron. “And I am grateful to him for telling me. He came to see me yesterday, to pay his respects, seeing as I am, as you know, dying. Which is, in fact, another truth. And don’t you dare tell him off, young lady, witch or otherwise. Promise me?”

Tiffany knew that the long lie had hurt her father. She’d never really worried about it, but it had worried him.

“Yes sir, I promise.” (pp. 73–79)

That is a long excerpt, but only about a third of the conversation. Its staging and ending both play into the local suspicion of witches, and set in motion events that put Tiffany and the Chalk in grave peril. Not every scene in I Shall Wear Midnight is as brilliant, but many of them are. This is a great book.