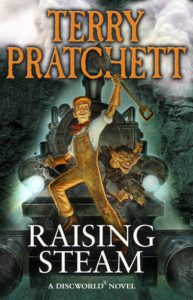

Why was Raising Steam, the penultimate Discworld novel, so much better than I expected? I had reason to worry. It clocks in at 475 pages, and for the last 10 books, I have much preferred the shorter ones to the longer ones. Both of Raising Steam‘s immediate non-YA predecessors, Unseen Academicals and Snuff, had seemed particularly self-indulgent. It’s programmatic: Pratchett has written about the post office, banking, and foot-the-ball; now he is going to write about railroads. It takes Moist van Lipwig as its central character, but Moist is not so much a character as a show and a collection of enthusiasms. He’s heaps better to read about than Rincewind, of course, but he’s nowhere near as interesting a creation as Captain Vimes, Granny Weatherwax (or even Nanny Ogg), or Tiffany Aching. The start is a bit shaky, too. Pratchett writes the dialog of Dick Simnal, the most important new character in Raising Steam, in the thickest dialect of any character that I can think of in all the Discworld books. I’m not sure what Pratchett is getting at with the dialect, unless it is referring to a specific regional English origin for the character, at the price of baffling anyone outside of England. He has managed to convey the humble origins of Captain Vimes and many other characters, or the country life in Lancre without resorting to ostentatious dialect.

With all of these factors arrayed against it, Raising Steam should just limp along as a serviceable late-Discworld book, a late-afternoon local on a line that is soon to be discontinued. But no, it works, splendidly, maybe even gloriously, barreling along its narrative tracks to a climax that’s thrilling and an ending that’s satisfying. Why? How?

First and foremost, Pratchett lets the story move, both in time and in space. The action of Unseen Academicals and Snuff takes place within a very short amount of time, a matter of a few days in each one, and within a narrow geography. In Raising Steam, Pratchett catches the spirit of the railways and has people going to different places, wanting to go different places, and doing their best to get to all of them faster and in greater comfort. The weeks that Moist spends negotiating with landholders in Quirm pass by in just a few paragraphs. It is important to the story that the negotiations take place, but Pratchett does not lavish the kind of detail on them that he had on secondary developments in other recent books. The Ankh-Morpork and Sto Plains Hygienic Railway develops far faster than rail travel did in England or the other industrializing countries, but that’s fine for the narrative, and it’s not so fast that readers fail to have the sense of a new era taking time to build up, well, steam.

Second, the major action mostly arises from the characters. Of course Vetinari, the ruling Patrician of Ankh-Morpork, would push Moist in the direction of the new railway, but it’s also exactly the kind of venture that Moist would seek out for himself. The great railway promoters of history were flimflam men not very different from Moist van Lipwig, and so he is a natural fit. Another major character behind the rise of the railway is Harry King, a brass-knuckle entrepreneur who has made a fortune in Ankh-Morpork’s nightsoil business and other less savory businesses. He first joined forces with Moist in rescuing the bank in Making Money, and Raising Steam shows more of his quest for respectability. King is rich, but the railway offers him the chance to go down in history as the first rail baron rather than just a lord of the muck. King also reads a lot like historical magnates, and if the former bruiser turns out to have a bigger heart for workers than his non-fictional counterparts, I put it down to Pratchett wanting to show certain aspects of the world as they could be. Dick Simnal, the engineer who invented Discworld’s locomotive and so much more besides, is also shown as savvier than his simple country boy act. These hard-driving characters bring speed and motion to a narrative that thrives on precisely that kind of energy.

Third, there’s a good case to be made for Raising Steam as the final Discworld novel, with The Shepherd’s Crown as a coda. Far from an elegy, though, the book is a culmination of long-term developments and a gathering of many of Pratchett’s best characters. (Captain Carrot, however, is conspicuously absent, and his absence is one of the most glaring holes in the book’s plot. Much of the danger in the book arises from the efforts of renegade dwarfs, known as grags, who cast themselves as guardians of tradition and worked to sabotage the railroad. Carrot, as a dwarf himself, would have led efforts to infiltrate the grags’ networks and block their attempts.) Moist has center stage, but once the action turns to getting a precious cargo to Uberwald at top speed and in the face of criminal opposition, Commander Vimes joins the train’s crew and brings several familiar faces from the Watch with him. Vetinari himself is more visible as a character than in any other book. I think that I prefer him to be a force in the background, but bringing him into the spotlight is consistent with Pratchett’s overall theme of progress. The railroad itself is a culmination of the technology that Pratchett has steadily introduced to the fantasy-medieval setting of the Discworld. The series began in an apparently unchanging world of wizards, a human-centered city, travel that was never faster than a horse unless magic was involved, mechanical power provided at best by wind and water wheels, and communication limited by the speed of travel (again, unless magic was involved). It ends with a multi-species city grappling with integration and equality, rapid communications networks, rail travel on the verge of tying the continent together, steam engines making their way into new applications, and the idea of automobiles clearly taking shape in some tinkerers’ minds. Modernity is coming to the Disc. As Vetinari puts it, “What next? What little thing will change the world because the little tinkers carried on tinkering?” (p. 475)

Fourth, there are still some great flourishes in Pratchett’s writing, which has more zip than it did in Snuff. “Harry King was close to incandescent at the best of times, but the state of mind he was in when he heard the news of the massacre could only be described as volcanic: one of those slumbering volcanoes that suddenly go off pop and the calm sea is instantly awash with dirty pumice and surprised people in togas.” (p. 223) The extended train chase in the later parts of the book is terrific, and its climax is very nearly perfect, a lovely blend of events that could only take place on the Disc.

All in all, Moist, Vimes, the Watch, Vetinari, the Low King and many other characters go out on a high note, the long piercing steam whistle of progress and change.