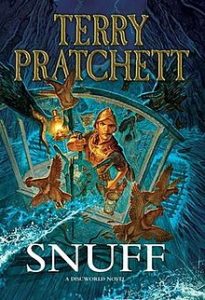

Snuff, the thirty-ninth Discworld book, turns out to be the last one starring Sam Vimes, who has gone a long way in the world since his first appearance in Guards! Guards! There will be one more Moist van Lipwig book, one more Tiffany Aching book (although I am still drafting my thoughts on I Shall Wear Midnight), and that is the end of the main sequence of Discworld books. By the time Snuff was published, Pratchett’s diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s had been public for four years; he would live for another four. I don’t know if Pratchett knew that Snuff would be his last outing with Vimes, but I tend to think not. There is nothing elegiac about it, and although there is an epilogue saying what happened later to various characters, it is almost exclusively concerned with minor characters whose futures support a point made by Vimes in the book’s middle and provide a few last laughs.

The book sends Vimes on a busman’s holiday, or more accurately, a policeman’s holiday. He is persuaded, well, practically ordered, to spend a couple of weeks at his wife Sibyl’s considerable estates in the countryside at some distance from Ankh-Morpork. She accompanies him to the manor house that she loved as a child but has not visited in eight or nine years. They bring along their son, Young Sam, not least so that he may have some of the same treasured childhood experiences that Sibyl recalls so fondly.

Vimes is out of his element. He is a city boy, through and through, and he finds the countryside vaguely unnerving. Nor is he much better with the people. He is quite used to being in charge as commander of the Watch, but he is not at all accustomed to being lord of the manor. His egalitarian instincts clash with what the people expect from someone at the top of the hierarchy, and he is equally clueless about the ranks and rivalries among all of the people who serve him and his family on the estate. Sibyl, of course, is to the manor born, and she prevents Vimes from making greater mistakes, even as she guides him to a place in country society.

All is not well, or it would be a very short book. During a dinner party, Vimes is told by one of the local gentry how quiet things are and how little there could be to interest someone who is used to the criminality of the big city. Vimes’ ears immediately prick up. Sometime later, he accepts a challenge to a fistfight from the local blacksmith who has egalitarian views similar to Vimes’ and isn’t afraid at all to share them at great volume and with great resentment. The blacksmith, Jethro, is young and strong and fast, but he has not had the decades of fighting people who are actually trying to kill him that Vimes has had, and it’s a short and one-sided fight.

Vimes follows up by buying drinks for the assembled crowd, and it’s score two for the local landed gentry, who are not only quick and combative but generous to their people. Vimes, though, senses that Jethro has more specific grievances, and the two of them arrange to meet at midnight on an isolated hill so that Vimes may hear what Jethro is reluctant to say in front of the crowd.

Jethro, however, goes missing, and the only thing that Vimes finds at the top of the hill is a great deal of blood. The next morning, the local constable attempts to take Vimes into custody on suspicion of murder.

With that, events are well and truly underway. Whose interests has Vimes impinged on enough to try to set him up? What has been happening to the local goblins? Are goblins as horrible and mindless as practically everyone on the Disc seems to think? (It is no great surprise that the answer to this question is No.) How will Vimes make the connections and sort out the situation? At this point in the series, there is no doubt that he will, but the joy is in seeing just how.

There is joy in seeing how Vimes sets things to rights, there is good farce, adventure and wry observation along the way (Vimes is considering dropping in on a local person who is the author of very popular children’s books, thinking, “and she is a writer, so I expect she’ll be quite glad of the interruption” [p. 217]), but for the first time I found myself sometimes rooting against Sam Vimes. Not to the point of hoping that he fails or hoping that the villains succeed — they are villainous, after all — but I thought that he is coming awfully close to what he has long despised in the powerful. The way he threatens people, the way he uses his authority both as local Duke and as Commander of the Ankh-Morpork Watch are perhaps different in degree from how the local magistrates arrogate the law to their persons but not sufficiently different in kind for me to be wholly on Vimes’ side. Pratchett has shown readers for several books Vimes’ bedrock decency, how he has not forgotten where he came from, how he knows the rule of law is more important than any ruler, but in Snuff Pratchett also shows a Vimes who is willing to get far ahead of the law in pursuit of what his instincts tell him is justice. I don’t think that a future Vimes book would have been a tragedy, with Commander Sir Samuel Vimes, Duke of Ankh, succumbing to the hubris of his own virtue — mostly because that is not the kind of book that Pratchett writes — but that aspect of the character is present, and it’s troublingly visible in Snuff.

Vimes’ decency is better shown in the example of Watch members he has brought up in the force, as when Cheery Longbottom, a dwarf, is questioning someone who is a smuggler and possibly involved with what happened to the goblins. “Cheery was aware that Commander Vimes didn’t like the phrase ‘The innocent have nothing to fear,’ believing the innocent had everything to fear, mostly from the guilty but in the longer term even more from those who say things like ‘The innocent have nothing to fear.'” (p. 298) The struggle between privilege (privilegium, private law) and universally applicable law is as real in Discworld as it was in early modern Europe — and in some instances, even today — but privilege is slowly receding thanks to people like Vimes and Cheery.

I like Discworld books better when they are closer to 300 pages than to 500, and at 475 pages Snuff is no exception. Pratchett gets to show all of the elements that he wants, and to extend incidents for as long as he wants, and I can’t help but think that I would prefer to be left wanting more or wondering a little bit about what happened. Did I really need to see all of how Wee Mad Arthur caught a bird to take him to Hondwanaland? Did the pub scenes need to be as long as they are? The in-story author of extremely popular children’s books is named Felicity Beedle; the apparent J.K. Rowling reference knocked me out of the book in the way that Pratchett puns usually don’t. I liked Snuff well enough, but I think I would have liked it more if there had been less of it.