One of the hard problems of writing far-future science fiction is just how strange humans of that era are likely to appear to present-day readers. Quite apart from the changes that technology and any move of setting from the terrestrial are likely to bring, the ways that societies change over time are likely to render humans of a time centuries hence nearly as alien as any actual aliens that appear in the stories. They won’t be unrecognizable — going in the other direction, readers still recognize people in, say, Dante, Homer and the epic of Gilgamesh — but they will be strange in ways both big and small, and things that are perfectly ordinary in a far future will be very difficult to comprehend to outsiders visiting from somewhen else.

Most of the time, authors ignore this problem for the sake of getting on with the stories they want to tell. Or they may rationalize their writing as something like an implicit translation from the idioms and manners of then into the usages of today. “Of course people in the twenty-sixth century won’t say ‘Perfectly cromulent,’ but they will have a functionally equivalent expression, and anyway I am writing for a contemporary audience so I use dialogue that is pleasing to present-day sensibilities.” There is also the point about the inevitability of authors writing as people of their time, with many of the assumptions and commonplaces of the era. It has been famously noted that Isaac Asimov, for example, could imagine a robot doing a man’s job, but not a woman doing the same.

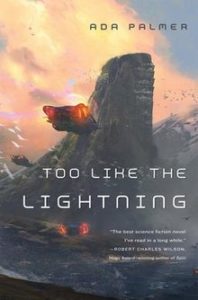

In Too Like the Lightning, Ada Palmer tackles this problem directly. “You will criticize me, reader, for writing in a style six hundred years removed from the events I describe, but you came to me for explanation of those days of transformation which left your world the world it is, and since it was the philosophy of the Eighteenth Century, heavy with optimism and ambition, whose abrupt revival birthed the recent revolution, so it is only in the language of the Enlightenment, rich with opinion and sentiment, that those days can be described. … It will be hard at first, but whether you are my contemporary still awed by the new order, or an historian gazing back at my Twenty-Fifth Century as remotely as I gaze back on the Eighteenth, you will find yourself more fluent in the language of the past than you imagined; we all are.” (p. 7) Fluent, too, in the language of the future. They care about things that strike us as unimportant, their daily interactions involve many of the same things, but are different in countless small ways that add up to a new society. Their motivations look odd, as of someone from a different culture, because of course that is exactly what they are.

Too Like the Lightning received my Hugo vote for best novel because of Palmer’s audacity and ambition in creating a world that is so thoroughly and consistently different from the present. Bits of the present are there in the future centuries — there is still a European Union, and still a King of Spain, for example — just as bits of the eighteenth century — the US Constitution — are still floating around and exerting influence today. Other bits of a more distant past have risen to greater prominence in the world Palmer describes: there is a Roman Emperor who wears the purple, while duellists are back and settling affairs of honor.

The main narrator is Mycroft Canner, a notorious criminal whose background is known to all of his contemporaries but not to readers. Part of Too Like the Lightning is the gradual exposition of Mycroft, his abilities, his importance in the global system, and, eventually, his terrible crimes. Another part of the book is the eruption into the technologically advanced world of a genuine miracle: a boy named Bridger who can bring inanimate objects to life, among other abilities. His existence and his powers have been kept secret by a members of a powerful family, but that is not likely to last indefinitely. Bridger’s miracles would astonish any society, but the world of the twenty-fifth century is one in which the public practice of religion has been eradicated (mostly voluntarily, after a series of devastating wars of religion) and human spiritual needs are met by a system of sensayers, counselors who draw on many traditions without favoring any. A miracle worker would challenge any status quo; it will surely upend this one.

Another part of the book is a bid to shake up the balance among the factions that command humanity’s allegiance. In the twenty-fifth, citizenship is untethered from territory, and people may join the polity that best suits them. Some few even choose to forego the benefits of law entirely, becoming blacklaws, not bound to respect the rules of society but equally free of their protections. There is a rough equilibrium among the Hives that most humans belong to, but privileged data that Mycroft has access to suggest that some people are working to upend the balance.

Noting the thematic threads of Too Like the Lightning makes the book seem more programmatic than it is. The book is dense and detailed, pulling a reader deep into its world with the deceptively simple tactic of describing that world as it appears to its inhabitants. Too Like the Lightning is also the first part of a much larger work. The book’s closing notes that it is the first half of Mycroft Canner’s history, which is continued in Seven Surrenders. That volume is followed by a “chronicle of the crisis still unfolding,” told in The Will To Battle and Perhaps the Stars, which last is expected to be published in 2019. Palmer is writing on a scale to match her thematic ambition, and it is glorious.

2 comments

Ooh, I got this courtesy of Tor a few months ago! Your review is a beacon light towards choosing it as I swim here in the murky depths of all my other reading. Soooooon.

Author

It’s not easy, and it’s not breezy, but it is trying to do big things, so, props for that. I put it down for long-ish stretches, but then went and swallowed big chunks of pages when I did pick it up again. My mileage varied, even within the book.