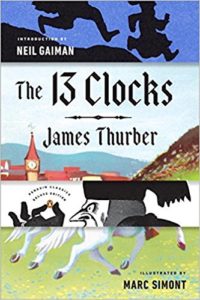

I am sure that I picked up The 13 Clocks because of the positive things that Neil Gaiman said about it among his reviews in The View from the Cheap Seats. I don’t have that text to hand just now, but I do have the introduction that he wrote to Thurber’s tale, even though he closes it by saying that the story does not need one. Gaiman says it’s probably the best book in the world, “And if it’s not the best book, then it’s still very much like nothing anyone has ever seen before, and, to the best of my knowledge, no one’s ever really seen anything like it since.” (p. ix)

“Once upon a time, in a gloomy castle on a lonely hill, where there were thirteen clocks that wouldn’t go, there lived a cold, aggressive Duke, and his niece, the Princess Saralinda.” (p. 1) The Duke is wonderfully bad. “One eye wore a velvet patch; the other glittered through a monocle which made half his body seem closer to you than the other half. He had lost one eye when he was twelve, for he was fond of peering into nests and lairs in search of birds and animals to mail. One afternoon, a mother shrike had mauled him first. His nights were spent in evil dreams, and his days were given to wicked schemes.” (pp. 1–2)

The story is in a fairy-tale register, leavened by absurdity and words both invented and inventive. It is also, as Gaiman notes, very short. “When I was a young writer, I liked to imagine that I was paying someone for every word I wrote, rather than being paid for it; it was a fine way to discipline myself to use only those words I needed.” (pp. x–xi)

The Duke, naturally, does not want to let anyone marry the Princess. Nevertheless, he has to allow princes to try to win her hand. In turn, he is allowed to set them tasks, and being what he is, he sets them impossible tasks, which is hard. “What makes it even harder is her uncle’s scorn and sword,” sneered a tale-teller. “He will slit you from your guggle to your zatch.” (p. 8)

There aren’t any surprises in this story, except on every page. There is a Golux, who “wore an indescribable hat, his eye were wide and astonished, as if everything were happening for the first time, and he had a dark, describable beard.” (p. 13) More people speak in rhyme than one would at first think, and much is said on the related subjects of tears and jewels. In the end, which is never far away, logic and the 13 clocks both play a role, neither of which works as expected. There is even, perhaps, just maybe, a gleaming glimpse of Ever After.