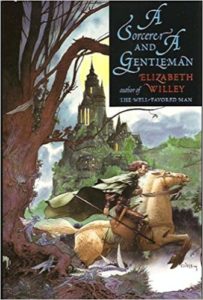

A Sorcerer and a Gentleman. One character who is both? Or two characters and one of each? Elizabeth Willey’s second novel, set in the same multiverse as The Well-Favored Man, offers numerous candidates for each appellation. She starts her story with an unknown person and the “proverb, often quoted but seldom applied, that all a gentleman needs to travel is a good cloak, a good horse, and a good sword.” In her second paragraph, she spells out what is more commonly applied, by detailing what a gentleman with just those three things lacks: “This man has no baggage but the saddlebags on his horse; he is alone, without a single servant to attend him; moreover, he is on horseback rather than in a carriage with the fine horse ridden by his lackey; and furthermore, he is plainly galloping … and his hair is blown about and his clothing disordered by the exercise. Lastly and most tellingly, it is night-time … long after sundown, a time when any true gentleman would long since have been snugly established in his chosen inn for the night with a good dinner and a bottle of wine.” (p. 9)

Having informed her readers that she will be playing with expectations about gentlemen, Willey then switches to a sorcerer, Prospero. Like the other Prospero, he is in exile, denied his rightful throne by a usurping brother. He, too, commands magical servants called Ariel and Caliban. He speaks less often in iambic pentameter than he did in The Well-Favored Man, but he does often enough for his mode of speech to be distinctive among this book’s characters. Unlike the other Prospero, this one has a daughter named Freia. She has accompanied him in exile to Argylle, a land he has either discovered or created, or perhaps a bit of both, with assistance from the magic of the Spring, which has given him command over the element of water. Prospero’s original home, Landuc, is in the realm of the Well of Fire. Other events not seen in the book have given him power over earth via the Stone in Phesaotois; he is also named Duke of Winds, though Willey does not say how he came by this title.

Willey next introduces Prince Josquin, and by way of accessories to him, the Emperor and Empress. Josquin is by definition a gentleman, but his first scene finds him recovering from prostration, and not from the usual pursuit of too much wine, but rather because another gentleman has played him false and caused him to fall into deep sleep for several days. Was the false player the person seen at the very beginning, fleeing with horse, cloak and sword? Circumstances suggest he was; they further suggest that he worked at least a minor sorcery on Josquin, quite apart from whatever charms caused the two of them to retire alone to the prince’s chambers.

The title can be weighed against each of the male characters as he is introduced, and kept in mind as events draw reactions from the people Willey depicts on the page. Who is a sorcerer? Who is a gentleman? Does the one preclude the other? Are these characters as they seem? Thinking back, I also wonder what questions Willey would pose for her female characters. They are equally vivid — Freia at once fierce and vulnerable, Luneté the Countess of Lys an enthusiastic young bride and mistress of her own realm, the sorceress Odile Prospero’s peer, and several others. Though Willey has chosen to tell a story mostly about the men of the worlds she creates, neither readers nor male characters should underestimate the women.

What story is she telling? One of the things that I liked most about this book is also one of things that kept me from being too enthusiastic about it early on: it isn’t just one kind of story. This is a setting that feels as if it had started long before the present volume opened and will continue well after the final page is turned. Likewise, the characters who play minor roles clearly have their own tales and interests. Where they intersect with what Willey wishes to show, they appear in A Sorcerer and a Gentleman, but there are many more tales that could be told.

The main conflict arises from Prospero’s attempt to wrest the throne from his brother, Emperor Avril. The attempt shown is not his first try, though as events transpire it may well be his last. Here is discussion with Freia after Prospero has told her of his intentions.

“We go to war with Landuc, that I may be King as is right.”

“But, Papa, why? Aren’t you happy here? You have people now; nobody is killing anybody—you told me it’s wrong to kill people! Won’t your people be killed too? They don’t have any quarrel with these Landuc people! Won’t they kill you? Please, Papa—don’t go to Landuc and have war. Everything is good here. Will you not stay here and be happy?” …

“Thou hast as much sense of honor as yon cabbages,” Prospero declared, scowling blackly at Freia, “and as much knowledge of policy and sorcery. ‘Tis right that I make war ‘pon Landuc, by any means to hand; I’m the King, by right of blood, for the King died without naming another heir, rather murdered himself and fouled the Well with his death. Say naught of these matters thou dost not understand! The world’s wagged amiss since that Avril insinuated himself upon a throne too great for him, beneath a crown too heavy. The Orb and Scepter are idle in his hands. The Roads ravel, the Bounds unbind; the very vigor of the world spends itself, useless, in the wastes. I, I have all the powers and every right to take it from him, to rule the place better than he, witling princeling, can. He’s no scholar, no sorcerer, knoweth naught of the Well: he’s unfit to rule. Now give me peace indeed: thy questions are a very battery of foolishness. Hearken to me, cease thy larking, thou’lt learn all needful to thee in good time.” (p. 67)

So have many would-be conquerors convinced themselves and brushed objections aside. It’s an interesting speech, too, because up to that point Willey had largely described Prospero as wise and creative. With that proclamation, she shows his ambition, shows the purpose of his creative work: seizing what he believes is rightly his.

While Prospero’s war provides the framework of the narrative, the wizard himself is offstage much of the time. Indeed, Willey spends a large portion of the book following Dewar, who is definitely a sorcerer and possibly a gentleman, who is set up as mostly a sympathetic character and who winds up opposed to Prospero for a significant part of the fighting. She also shows much of Ottaviano, of late a captain of guards who has persuaded the Countess of Lys to marry him as soon as she attains her majority, and who has spirited her away from her imperial guardian to her home city for this very reason. At first Otto appears a bit of a meathead; later Willey shows the love shared by Otto and the Countess, which is real but not uncomplicated; still later she shows the consequences of his shortcomings.

The first third or so of the book felt a bit distant, though the individual events of the stories were interesting. I’m glad I stayed with it. Reflecting on A Sorcerer and a Gentleman has shed light on some the things I thought odd about The Well-Favored Man. Our world makes a couple of cameo appearances in the multiverse shaped by Well and Spring and Stone — one character has what appears to be a Swiss army knife, and a pair briefly retreat to our world — not unlike its appearances in the Amber series, to which Willey’s works owe a considerable debt. The main conflict is mostly resolved but many other incidentals are not. I was not, however, left with a sense of things hanging. Rather, I felt that I had looked in on a part of a history, one that quite naturally continues in all of its places even after one set of battles has ended.

The title, finally, misleads in one way. The book does not concern itself with a sorcerer and a gentleman, but with many possible examples of each. Luring the reader in with a hint of unity, Willey instead delivers a multiplicity that is much more interesting than a single tale.