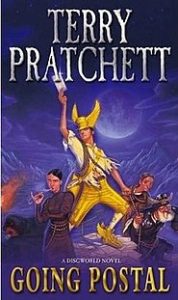

At different parts in the Discworld books, Terry Pratchett considers what might happen when something like a modern technology appears in the magical, quasi-medieval societies of the Disc. Moving Pictures was the first of these, back at the 10th book in the set, and they become more common later in the run. The Truth introduces newspapers. Going Postal features a revival of Ankh-Morpork’s Royal Mail. The clacks, a semaphore system that has effects a bit like the telegraph and the internet did in our world, was introduced in The Fifth Elephant, though it was not the main topic of the story. Looking at what other people have written, I see that I have a few more ahead of me in the eight books that remain after Going Postal.

I started out skeptical about Going Postal. The setup struck me as a deus ex Vetinari: using the powers and abilities of Ankh-Morpork’s ruling Patrician to set the story in motion, rather than having it emerge more naturally from the setting or from previously established characters. The authorial hand is very visible in the beginning. Pratchett wants a certain kind of character doing a particular thing with the postal service. On the other hand, the kind of character Pratchett wants at the center of this book is interesting: Moist van Lipwig is a con man, a thief, a reprobate. He has been looking out for number one so long that looking for a way to get away with the loot is a reflex.

The clacks have been taken over by a bunch of caricature capitalists, and Vetinari wants some competition in the business of delivering messages, so he puts Lipwig in charge of reviving the ancient postal service that was once the pride of Ankh-Morpork but has since fallen onto hard times. It’s not so much administrative ability that’s necessary to restoring the post but rather the ability to inspire people to believe that it will function. And getting people to believe things is Lipwig’s specialty.

I think that Going Postal, like Monstrous Regiment, would have been better if it had been shorter. In particular, the first third of the novel feels like it is wandering around, with comic bits playing out longer and more slowly than necessary, and with other developments unfolding at a pace that’s more languid than leisurely. It’s Pratchett, so it’s never hard going, but it’s looser than earlier Discworld books, not always to its benefit.

On the other hand, there are funny bits and arch observations throughout, and the action really is headed somewhere interesting. In some ways, Going Postal is an extended meditation on belief — inspiring it, harnessing it, and taking advantage of it.

“You want to deliver this letter to [the god] Offler?” [the priest] said, yawning. An envelope had been placed in his hand.

“It’s addressed to him,” said Moist. “And correctly stamped. A smartly written letter always gets attention. I’ve also brought a pound of sausages, which I believe is customary. Crocodiles [the god’s aspect] love sausages.”

“Strictly speaking, you see, it’s prayers that go up to the gods,” said the priest doubtfully. …

“As I understand it,” said Moist, “the gift of sausages of Offler by being fried, yes? And the spirit of the sausages ascends unto Offler by means of the smell? And then you eat the sausages?”

“Ah, no. Not exactly. Not at all,” said the young priest, who knew this one. “It might look like that to the uninitiated, but, as you say, the true sausagidity goes straight to Offler. He, of course, eats the spirit of the sausages. We eat the mere earthly shell, which believe me turns to dust and ashes in our mouths.”

“That would explain why the smell of sausages is always better than the actual sausage, then?” said Moist. “I’ve often noticed that.”

The priest was impressed. “Are you a theologian, sir?”

“I’m in … a similar line of work,” said Moist (pp. 332-33)

Pratchett had also been listening to the women in his life, and believing them. Moist is in a disreputable bar, meeting up with a woman from the golem trade, Miss Dearheart.

When [Moist] returned, his seat was occupied by a Currently Friendly Drunk. Moist recognized the type, and the operative word was “currently.” Miss Dearheart was leaning back to avoid his attentions and more probably his breath.

Moist heard the familiar cry of the generously sloshed.

“What … right? What I’m saying is, right, what I’m saying, nahrmean, why won’t you, right, gimme a kiss, right? All I’m saying is—” (p. 292)

Miss Dearheart drives a spiky heel into the drunk’s foot, and tells him how hard she can kick with the other spike.

With great care the man stood up, turned and, without a backward glance, lurched unsteadily away.

“Can I bother you?” said Moist. Miss Dearheart nodded, and he sat down, with his legs crossed. “He was only a drunk,” he ventured.

“Yes, men say that sort of thing,” said Miss Dearheart. (p. 393)

Once it gets underway, though, Going Postal is zippy fun with just enough seriousness to keep the deliveries from going astray. Much of that comes from Moist looking at the world with new eyes, as he sees both the perils and the possibilities of having people truly believe in him for ends greater than quick cash.