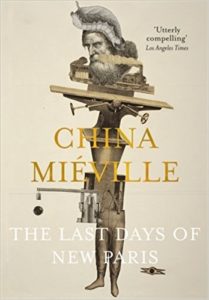

I should not have taken as long as I did to get through China Miéville’s novella, The Last Days of New Paris. The main story is less than 180 pages; the afterword tacks on another 15 or so, and I mostly did not read the notes that are appended afterward. That the words “get through” are the first that spring to mind is telling, though I suppose the larger lesson is that Miéville’s work is hit-or-miss for me. I’ve read eight of his 13 published books (tried a ninth, Un Lun Dun, but bounced). Perdido Street Station felt like a revelation when I read it; The City & The City is terrific, an amazing mash-up of Cold War, maybe-magic, and the human tendency not to see what we don’t want to see. I’m not sure that it fulfills all of its promises, but even getting nine-tenths of the way there is an achievement. I’ve been told that Embassytown is as good as these two; it’s on my shelf of books to read, and I’m looking forward to reading it at some point. On the other hand, This Census-Taker didn’t do much for me.

In the world of The Last Days of New Paris, a massive, mystical bomb exploded in the French capital in 1941, releasing strange energies into streets newly occupied by the invading Wehrmacht. Within a certain yet uncertain radius around the point of detonation, the laws of physics have been pushed aside and Surrealist works have manifested themselves into reality. The top half of the Eiffel tower remains suspended in midair though the bottom half has been destroyed. The novella opens with one of these manifestations, which Miéville calls manifs, headed toward a German barricade somewhere in the streets of Paris. The manif is a “torso, jutted from the bicycle itself, its moving prow, a figurehead where handlebars should be. She was extruded from the metal. She pushed her arms backward and they curled at the ends like coral. She stretched her neck and widened her eyes.” (p. 4) Another woman is riding the manif, which is a thing that Miéville’s narrator, Thibaut, says should not be. He is not able to find out much more. The Germans shoot both manif and rider. Thibaut scampers from his hiding place long enough to hear the rider’s dying words and receive a playing card from her.

Half of Miéville’s narrative follows Thibaut as a resistance fighter in Surreal Paris in 1950. The Second World War continues, although the outlines of that struggle outside of Paris remain vague. The Germans do not control all of the city, but they have managed to seal it off, containing the mystical energies and manifs within the city’s limits. The other half of the narrative takes place nine years earlier, mostly in and around Marseilles, and recounts the events that led to the creation and detonation of the S-Bomb that so changed Paris.

The resistance in Paris is as splintered as the art world it partially mirrors. They are not likely to betray each other to the Germans, but they are unlikely to help each other out even in a firefight against the occupiers. The fight continues, but without much hope of achieving anything other than imposing a few casualties on the mighty Wehrmacht. I think this isolation is one of the things that limited my interest in what happened to Thibaut and his comrades. Fighting is about all that Miéville shows them doing, and yet their fighting is oddly ritualized. The closest comparison to events in this world’s WWII are the Jewish uprisings in various ghettos: sealed off from the outside world, improvised weapons against a war machine that commanded the resources of a continent, doomed from the onset and yet compelled to resist to show that they would not simply be herded to their deaths. But in the Paris of the S-Bomb, resistance has continued for nine years, has somehow evolved into an almost ritual game of cat and manif. I don’t see how the war in Europe lasts five years longer than it did, and the absence of any indication within the story of how stasis had come to the larger fight threw me out of the novella far more than the Surrealist manifs, or the literal demons and devils who turn up later on in its pages.

Miéville brings the backstory up to the time of the explosion and gets Thibaut to something like a break in his tale, and that’s the end of The Last Days of New Paris. Then he appends an afterword that’s a framing narrative like something from the earliest days of scientific romance, stating that he wrote The Last Days of New Paris based on a curious set of interviews that took place in the autumn of 2012. In this telling, the Miéville of the afterword comes to believe that his interlocutor is Thibaut, thus implying that the story “really” happened. Whatever. There are also notes that discuss the real-world analogs or origins of the manifs and other elements of the story. I skimmed a few of them to see whether there was another narrative strung among the notes, but no.