Time for some short takes, to mostly clear the desk for the coming year.

The Inexplicables by Cherie Priest. In the fourth of her five Clockwork Century novels, Priest takes a stab at telling her story mostly from the point of view of an unsympathetic narrator. Rector Sherman is an addict, hooked on the “sap,” a distillation of the strange gas that has blighted frontier Seattle and turns people who breathe too much of it into zombies. Priest also hints, as she did in Ganymede, that the same fate awaits people who take sap for too long. The action of the book turns on two developments behind the wall that has contained the gas and turned Seattle into a strange half-alive place, with monsters above ground, human settlement below, and zeppelins shuttling in and out with their illicit cargo. First, criminals from elsewhere have heard of the demise of Seattle’s previous kingpin and are trying to move in on the territory. Second, a new kind of monster has appeared on the streets, bigger and more fearsome than the zombies. Priest brings the action, even if I figured out the mystery well in advance. I also liked the artistic stretch of telling this kind of story through a character who’s basically a jerk. It’s not easy to pull off, and she does it well.

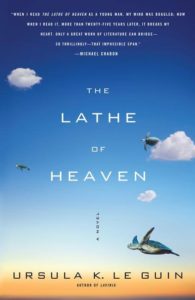

The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin. Some of George Orr’s dreams come true. Not in any trivial sense, but in the sense of the whole of reality reshaping itself around his effective dreams. When he was younger, an aunt stayed too long at George’s house. He dreamed that she had died in a car accident, and woke up into a world in which she had been buried six months previously, after a crash, and had never come to visit. Only George remembers the previous reality, and that only dimly sometimes. Fearing his power, trying to suppress his dreams, and losing his sanity, George goes to a psychiatrist who specializes in dream and sleep. The doctor has no such fears and no scruples. He uses hypnosis to steer George’s dreams, and he uses George’s power to reshape the world, alleviating overpopulation, eliminating racism, and more. Dystopias ensue. In its approach to sleep research, drugs, and mental health The Lathe of Heaven is a very 1970s book. Overpopulation as a major concern is also very much of the era in which it was written. On the other hand, the considerations of unlimited power, of human relationships, of what makes a good world are perennial questions, and the situation that Le Guin has set up lets her cut directly to the heart of these matters.

The Woman Who Walked in Sunshine by Alexander McCall Smith. In this tale of the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, Mma Ramotswe is persuaded to take a holiday. She takes a few days away from her office, but like many founders and owners of a small business she finds it difficult to believe that things can go well in her absence. Events appear to bear out her worries, as one of the staff comes to her in confidence, saying that the acting director has saddled him with responsibility but not the means to undertake his appointed tasks. Of such seemingly small things are these lovely books made, populated with characters that readers cherish, enmeshed in the natural conflicts of being human in a complicated world. Some appearances are deceiving, while others are not but the characters do not wish to see what is plainly in front of them. Some characters make mistakes, and they may or may not learn from them, as depends on their nature. I love the warmth of these books, and while I suspect that a parody of them would be hilarious, I cannot bring myself to be cynical about them. I have two more to go before I am fully caught up, but I suspect that Smith may write another before then, and that is perfectly fine with me.

Black Light by Elizabeth Hand. I very nearly pronounced the Eight Deadly Words, but I was reading this on my phone, the pages were short, I just kept turning, and pretty soon I was done. The story is set in a sorta Lovecraftian town in New York’s Hudson Valley, a town that is home to many theater, radio and television people — not too far from the city where they find work, but far enough to be a rural retreat. The town also has an odd history, witches, a nearby village that was inundated when a dam was built, massacres during colonial times, and suchlike. It will not surprise readers that much of what was thought to be legend turns out to be true, nor that the Dionysian movie director whose decadent party forms most of the novel’s second half, turns out to be very Dionysian indeed. Apparently Black Light was a New York Times notable book in 1999, its year of publication, so somebody liked it a lot. Just not me.

China: A History by Harold M. Tanner. I’ve not actually finished this one, but I can clearly see where it’s going and what the journey will be like. This is a one-volume history of China, and it looks to me like it is set up to be a textbook for a single-semester undergraduate course on the same subject. That’s perfectly fine. It’s a mostly political history, with something like a fifth of the text looking specifically at cultural aspects, including art, ideas, and philosophies. He does not neglect the economics, technology, or climate that underpinned political arrangements, but they are clearly subordinate in this account. Tanner’s writing is clear and serviceable. His overarching themes include centralization versus disintegration, cultural variety versus uniformity, how the long past is used to support arguments about present arrangements, and competing schools of thought about right action. The book was published in 2009, so naturally it opens with observations about the 2008 Summer Olympics. When I get to the end, I suppose I will see how well he handles the question of whether history points toward the present he was writing in. On the whole, I expect that it will — to the extent that I can remember what I am reading — provide a decent framework to hang future reading about China on. Years ago, I read Jonathan Spence’s In Search of Modern China, and that was actually very good and more detailed than this book, but of course it begins its narrative in 1648 or so, whereas Tanner goes back as far as the archeological record will allow (but briskly moves into recorded history). My top recommendation, though, would be River Town by Peter Hessler. First of all, Hessler is a brilliant writer. Second, River Town is about his own introduction to China, so readers learn about past and present as he does. It’s vivid, it links the private and the public aspects of China as seen by an outsider, and it’s a demonstration that contemporary China is changing so rapidly that this account describes an era in many ways already past. Tanner provides a framework; authors like Hessler fill the frame with life.

1 comments

I read Black Light recently and I am surprised it was a NYT Notable book. I finished it, but I was full of “meh”…