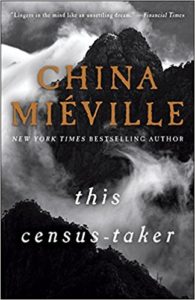

This Census-Taker, by China Miéville, did not add up for me. If it were not a Hugo finalist, if I had not read and liked close to half a dozen of his other works, I would have pronounced the Eight Deadly Words and set the book aside. Miéville is aiming for the mythic, but mythic is not where I am as a reader just now, and so what I think was meant to be archetypal read more as vague to me.

The story is set in and near a small town located in a remote mountainous region. The narrator, who slips among first- second- and third-person storytelling, is the only child of an odd couple who live atop a flinty hill some distance from the town. The wider setting features signs of a civilizational collapse, with people scraping by amidst scenes of technology that no longer works and a population much reduced by circumstances that include war. The boy’s father makes keys that seem to have magical properties, though they may also be mainly psychological in their workings. The boy’s mother tends the hard-scrabble gardening that produces much of their basic needs. At the story’s opening, the boy runs screaming down into the town because one of his parents has killed the other, though just who killed whom are cast into immediate doubt by the boy’s state. Later, his father claims there wasn’t any killing at all. The narrative, told by the boy an unspecified amount of time later when he is an adult, moves about before and after the opening scene, showing events leading up to it, the months immediately after, and how he came to leave the town.

+++

This Census-Taker was the twelfth bit of Hugo reading I have done this year, and the ninth I have written about.