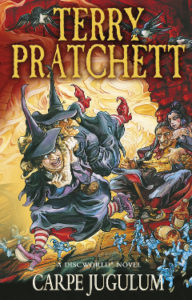

Somewhere I had read that Maskerade was the last Discworld book featuring the Lancre witches. Worse, I believed it, so I was both a little surprised and a lot pleased to pick up Carpe Jugulum and find that they were back. Pratchett dispensed with the traditional opening — “When shall we three meet again?” — because numbers are still something of a sore point for his witches. Magrat is still a Queen, as she has been since the end of Lords and Ladies, and Agnes, a.k.a. Perdita, is of two minds about the whole witchy business.

Pratchett combines three main elements to set the machinery of Carpe Jugulum in motion. First, he has the structural problem that Granny Weatherwax has grown considerably in power since she was first introduced to readers back in Equal Rites. As Nanny Ogg noted in Maskerade, witches whose power grew unchecked tended to come to bad ends, or to just go away somewhere far from mortal ken. Granny is still very much in the danger zone in this regard. Second, the King and Queen are about to have their first child, so naturally there will be a naming ceremony. The witches are invited, but it wouldn’t be a proper story if all the invitations arrived and all the witches attended and none of them got offended and nothing went wrong, would it? Third, as the title implies, vampires show up. This particular vampiric family is looking to expand their demesne and has chosen Lancre as a tasty addition.

By way of setting up all three, Pratchett writes a scene that’s as deft and devastating as anything I can think of in Discworld to this point. Granny Weatherwax has been called to help with a birth. The midwife sent someone a-running because things were all going wrong.

Witches always lived on the edges of things. She felt the tingle in her hands. It was not just from the frosty air. There was an edge somewhere. Something was beginning. […]

“Evening, Mr Ivy,” she said, leaping off [her broom]. “Upstairs, is she?”

“In the barn,” said Ivy flatly. “The cow kicked her … hard.”

Granny’s expression stayed impassive.

“We shall see,” she said, “what may be done.”

In the barn, one look at Mrs Patternoster [the midwife] told her how little that might now be. […]

“It’s bad,” she whispered, as Granny looked at the moaning figure on the straw. “I reckon we’ll lose both of them … or maybe just one …”

There was, if you were listening for it, just the suggestion of a question in that sentence. Granny focused her mind.

“It’s a boy,” she said.

Mrs Patternoster didn’t bother to wonder how Granny knew, but her expression indicated that a little more weight had been added to a burden.

“I’d better go and put it to John Ivy, then,” she said.

She’d barely moved before Granny Weatherwax’s hand locked on her arm.

“He’s no part in this,” she said.

“But after all, he is the—”

“He’s no part in this.”

Mrs Patternoster looked into the blue stare and knew two things. One was that Mr Ivy had no part in this, and the other was that anything that happened in this barn was never, ever, going to be mentioned again.

“I think I can bring ’em to mind,” said Granny, letting go and rolling up her sleeves. “Pleasant couple, as I recall. He’s a good husband, by all accounts.” She poured warm water from its jug into the bowl that the midwife had set up on a manger.

Mrs Patternoster nodded.

“Of course, it’s difficult for a man working these steep lands alone,” Granny went on, washing her hands. Mrs Patternoster nodded again, mournfully.

“Well, I reckon you should take him into the cottage, Mrs Patternoster, and make him a cup of tea,” Granny commanded. “You can tell him I’m doing all that I can.”

This time the midwife nodded gratefully.

When she had fled, Granny laid a hand on Mrs Ivy’s damp forehead.

“Well now, Florence Ivy,” she said, “let us see what might be done. But first of all … no pain…”

As she moved her head she caught sight of the moon through the unglazed window. Between the light and the dark … well, sometimes that’s where you had to be.

INDEED.

Granny didn’t bother to turn around.

“I thought you’d be here,” she said, as she knelt down in the straw.

WHERE ELSE? said Death.

“Do you know who you’re here for?”

THAT IS NOT MY CHOICE. ON THE VERY EDGE YOU WILL ALWAYS FIND SOME UNCERTAINTY.

Granny felt the words in her head for several second, like little melting cubes of ice. On the very, very edge, then, there had to be … judgement.

“There’s too much damage here,” she said, at last. “Too much.”

A few minutes later she felt the life stream past her. Death had the decency to leave without a word.

When Mrs Patternoster tremulously knocked on the door and pushed it open, Granny was in the cow’s stall. The midwife saw her stand up holding a piece of thorn.

“Been in the beast’s leg all day,” she said. “No wonder it was fretful. Try and make sure he doesn’t kill the cow, you understand? They’ll need it.”

Mrs Patternoster glanced down at the rolled-up blanket in the straw. Granny had tactfully placed it out of sight of Mrs Ivy, who was sleeping now.

“I’ll tell him,” said Granny, brushing off her dress. “As for her, well, she’s strong and young and you know what to do. You keep an eye on her, and me or Nanny Ogg will drop in when we can. If she’s up to it, they may need a wet nurse up at the castle, and that may be good for everyone.”

It was doubtful that anyone in Slice would defy Granny Weatherwax, but Granny saw the faintest grey shadow of disapproval in the midwife’s expression.

“You still reckon I should’ve asked Mr Ivy?” she said.

“That’s what I would have done …” the midwife mumbled.

“You don’t like him? You think he’s a bad man?” said Granny, adjusting her hatpins.

“No!”

“Then what’s he ever done to me, that I should hurt him so?” (pp. 35–39)

So much to unpack in that scene. The edges, the beginning, the judgment: these are the things that the vampires will try to use against Granny Weatherwax as they try to move in on the little kingdom where she lives. The locally prevailing views of the relative value of men and women, and Granny’s views of those views. Mrs Patternoster already mournful, and then fleeing, leaving Granny as the only conscious person out at the very edge until Death arrives. Granny, in arrogance or compassion, taking the burden on herself, and then reminding the midwife what it would have meant to give that choice to Mr Ivy.

Though the tale gets more convoluted later on, at its heart, it is about Granny Weatherwax, and the choices she makes.

Some of the convolutions involve Quite Reverend Mightily-Praiseworthy-Are-Ye-Who-Exalteth-Om Oats, a priest of Om who has come to try to convert some of the people of Lancre. Others involve the invading vampire family who have newfangled ideas but a very oldfangled servant, Igor, who often laments that such things (whatever they are) would never have happened in the old count’s time. Each will play a key role in the series of confrontations that determine whether Lancre will become a vampire fiefdom outside of Uberwald. (And lest a reader think that just because Pratchett can write devastating scenes, that would ever become all that he does, he adds a note about Uberwald: “On the rare maps of the Ramtops that existed, it was spelled Überwald. But Lancre people had never got the hang of accents and certainly didn’t agree with trying to balance two dots on another letter, where they’d only roll off and cause unnecessary punctuation.)