The two main characters of A Closed and Common Orbit are learning what it is to be human. That’s not quire correct in one case; maybe it would be more correct to say that each is learning what it is like to be a person, with a fairly wide definition of what “person” means. They come at it from different ends, different directions and eventually meet on common, well, maybe not common ground but perhaps the common orbit of the title.

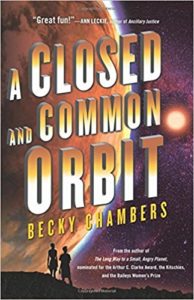

The book is a sequel to The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, which I have not read. A paragraph prefacing Orbit says that the current timeline in the story begins during the final events of Planet. It is possible that this discussion will contain spoilers for that book. I was not lost reading Orbit, so it’s not necessary to have read the previous book to enjoy the current one.

Lovelace — called Sidra in most of the book — is a ship’s AI downloaded into a highly illegal body kit for reasons not explained in the current story. She doesn’t like it. “Twenty-nine minutes before, she’d been housed in a ship, as she was designed to be. She’d had cameras in every corner, voxes in every room. She’d exsited in a web, with eyes both within in outside. A solid sphere of unblinking perception.” She doesn’t like it in the least. “Her vision was a cone, a narrow cone fixed straight ahead, with nothing — actual nothing — beyond its edges. Gravity was no longer something that happened within her … nor did it exist in the space around her, a gentle ambient folding around the ship’s outer hull. Now it was myopic glue, something that stuck feet to the floor and legs to the seat above it.” (p. 5)

Faced with such disconcerting input, such disappointing constricting input, Lovelace comes to the logical conclusion that the kit must be malfunctioning. No, Pepper assures her, that’s what being singular in a body is like. A body kit that, if discovered, would lead to many years of imprisonment for the people who have helped her into it, and erasure for the AI housed therein.

Lovelace looked closely at Pepper. She was tired, and they’d only just left the [previous ship]. There were still enforcement patrols to worry about, and backstories, and — “Why are you doing this? Why do this for me?”

Pepper chewed her lip. “It was the right thing to do. And I guess — I dunno. It’s one of those weird times when things balance out.” She shrugged and turned back to the console, gesturing commands.

“What do you mean?” Lovelace asked.

There was a pause, three seconds. Pepper’s eyes were on her hands, but she didn’t seem to be looking at them. “You’re an AI,” she said.

“And?”

“And … I was raised by one.” (p. 10)

That’s the bare bones of the set-up. Sidra, the name Lovelace chooses from a database of Earthen names, trying to figure out how to live in a body that does not match up with her sense of self, her sense of purpose, her previous lived experience. Pepper, who was once Jane 23, recounting the tale of how she came to be Pepper, and what an AI has to do with all of that.

I liked very much that Chambers has the confidence to tell a small story. The galaxy she depicts is large, full of spacecraft and stations and settlements, with numerous sentient species in what appears to be mostly peaceful coexistence. There are hints of larger political currents, but except for the existence of police powers that could arrest Pepper (and the others who are in on the secret) and erase Sidra, they do not play a role in shaping the plot. A Closed and Common Orbit is a story that takes place within the world that Chambers has set up, it is not a story of that world. The novel’s events are crucial to the characters, and that is sufficient to drive the narrative. They don’t have to save or change the world. They just have to save themselves, and that is enough.

Sidra’s story could also be read as one of a person who is not neurotypical learning how and why other people behave as they do, and learning to make compromises to get along with that while also looking for an environment that fits. Sidra has plenty of abstract knowledge of how sentients behave, but finds being one herself very challenging. She makes mistakes and endangers her friends not through malice, but by mistakes, and simply by thinking differently. It’s a bildungsroman, after a fashion, partly of maturing, partly of figuring out.

Pepper’s backstory reveals that she, too, is a made person. Her earliest memories place her as child slave labor kept in a factory by guardian robots, kept on-task by strong discipline. Part of those early stories are about how individuality emerges even among persons made to be all the same. They show how Pepper also had to consciously learn many things that people more normally socialized take for granted.

It would be too much to say that by the end both have everything figured out, but they have at least taken big steps. They have realized things about themselves and changed their own worlds a little bit, maneuvered into more stable orbits.

+++

A Closed and Common Orbit was the fourth bit of Hugo reading I have done this year, and the fifth I have written about.