One of the descriptions of Neil Gaiman that has stuck in my head is “reasonably facile writer.” He used the phrase in a New Yorker profile back in 2010, and there’s a British self-deprecating quality to the description, but there’s more than a little truth to it, too. Gaiman writes quickly, and with reasonable facility, and he puts a lot out into the world. He’s found his audience, and so he’s also asked to put a lot of different things out into the world, in addition to the stories he chooses to tell and the art he chooses to make.

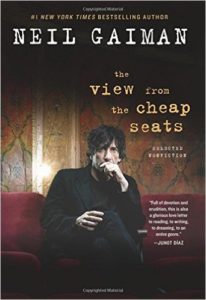

The View from the Cheap Seats collects several dozen of Gaiman’s publications on subjects and people that are near and dear to him. It is “a motley bunch of speeches and articles, introductions and essays. Some of them are serious and some of them are frivolous and some of them are earnest and some of them I wrote to try and make people listen.” (p. xvii) They didn’t always; he tried to tell comics distributors that they were in a bubble market just before it burst. The warning went over about as well as such things usually do. “Make Good Art,” his 2012 commencement address for the University of the Arts in Philadelphia “became one of the most widely distributed things I’ve ever done: the videos of it online have been watched many millions of times, and it is also available as a small book, designed by Chip Kidd.” (p. 459)

I enjoy sitting down and listening to Gaiman. I can’t tell if he writes with the apparent ease that only comes after half a dozen drafts, or if the thoughts simply flow to his keyboard in their reasonable fashion, or some combination of the two. No matter, really; he’s interesting, and he points me toward additional interesting authors and creators. Taken at face value, the pieces are mostly about art: writing and telling stories or making comics, movies and music. With a few exceptions, what Gaiman thinks about life comes across indirectly, revealed by what he chooses to highlight or what he chooses to let slide by.

There’s an art, too, in the construction of the book, how he moves from several credos near the beginning, through introductions to works in various fields, into portraits of fellow artists, whether writers or comics creators or filmmakers or musicians, before closing with what he calls “real things.” The very last piece is an appreciation of Terry Pratchett, who was a friend of Gaiman’s and who died not long before the book was together. The penultimate piece recounts visits to camps where refugees from the civil war in Syria were trying to put new lives together. It’s almost the only piece in the book that touches on political events; I did wonder what took him so long. There’s a splendid piece on the Dresden Dolls, a band that his second wife was half of for seven years; it captures the immediacy of performance, the depth of Amanda Palmer’s engagement with her arts, and how much that means to Gaiman. Several of the essays feature Palmer, or aspects of Gaiman’s relationship with her, particularly as two working artists. His children from his first marriage are mentioned from time to time; his first wife (Mary McGrath) not at all.

Most of The View from the Cheap Seats concerns the creative fields where Gaiman has worked: comics, fantasy, children’s books, fairy tales. Through the twenty years of writing here, Gaiman hasn’t forgotten what drew him to any of these fields, he’s still more at home in the cheap seats than among the glittering events that his popularity gains invitations to, as his items from the Sundance film festival make plain. Some of the essays show how these genres work; others just show his delight in one creator or another — Fritz Leiber, Diana Wynn Jones, Alan Moore, Tori Amos — and sometimes shows his subject in a new light, reflected through Gaiman’s own muse. Not bad for a reasonably facile writer.