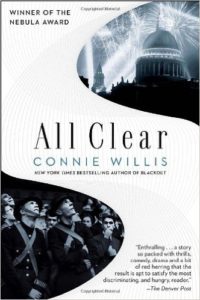

All Clear, which picks up right where Blackout left off and comprises the second part of an 1100-page story, would have been a brilliant book at about half or two-thirds of its 640-page length. The ending has emotional power; it resolves the main question running through the books and ties up the characters’ individual tales satisfyingly, but it’s a long way to get there. I like big books and I cannot lie, but even though I have just finished All Clear this afternoon I would be hard pressed to say what the characters were getting up to in the first 300 or so pages.

The three historians from the future who were separated through most of Blackout have found each other by the time All Clear begins. They are still cut off from 2060s Oxford, and they cannot understand why. Worse, a historian cannot visit the same day in the past twice, and so at least one of them who had a previous research assignment later in the war is facing a deadline in a very literal sense. Time is no longer on their side. They also convince themselves that the reason the drops are not opening and allowing them to return to the future is that they have somehow altered the course of history, and the Oxford that they knew in the future has ceased to exist. In the first parts of the novel, the historians react to their reunion and their joint predicament largely by retreating into their circle of three and cutting off most contact with the contemporaries with whom they had forged bonds in the previous book. That struck me as both bad behavior on their part and inconsistent with the way they had been portrayed up to that point. It also seemed an odd authorial choice, as interesting characters were mostly set aside for a series of wild goose chases. Another odd choice was to have the historians at least partly come to the conclusion that the continuum of history itself is trying to kill them and many of the people around them, in an attempt to prevent the historians from altering events. But when characters in a novel started talking about history taking specific actions, it was impossible for me not to see the hand of the author, and my suspension of disbelief started to fall apart.

It’s possible that Willis wanted readers to experience the length of wartime Britain in some way as the people of the period did, and that’s why the first half of the book felt like an uncertain slog, full of bombs and raids and destruction. It’s possible that her material just got away from her, as happens to the best of authors from time to time.

Another difficulty with this book is one faced by anyone writing about a subject as vast as the Second World War, or even the part of it that took place in southern England: either the cast of characters multiplies out of hand to reflect the massive movements of people in that time and place, or a smaller group of characters keep encountering each other in a most improbable way. Most of the time Willis does well with a limited cast, but as the novel went on it felt to me as if only a dozen or so people were there and kept bumping into each other, even though masses of people are implied both by the setting and by occasional descriptions. Further, there are an inordinate number of cliffhanger endings at the chapter breaks. That happened often enough that, for me, they started to lose their punch. Shortening All Clear would have limited both of these problems.

There are a lot of funny moments in the book; there are a lot of vivid moments of WWII. There are moving moments, and there are some of those that could not be achieved without the added element of time travel. All Clear never stops being a science fiction novel.

After the funeral, the rector asked Polly [one of the historians] again about scheduling a[nother funeral] service. “I could speak to the Reverend Mr. Unwin now, or perhaps you’d like to have it in some other church.”

Yes, Polly thought, St. Paul’s. It’s where all the heroes are: Wellington and Lord Nelson and Captain Faulknor. [He] should be there as well, though she knew they’d never allow it.

But she asked Mr. Humphreys anyway, and, to her surprise, he said that they could hold a small private service in the Chapel of St. Michael and St. George. …

He asked Polly what day she’d like to have the service, and she told him about Eileen [another historian]. “People often find death difficult to accept,” he said, shaking his head, “particularly when it is sudden. Is there someone she’s close to who could help her through this? Her mother or father, perhaps, or a friend from school?”

None of them has been born yet, Polly thought, going to Oxford Circus to attempt to persuade Eileen to return to Mrs. Rickett’s and get some sleep. Things couldn’t go on this way. Eileen was eating almost nothing and sleeping scarcely at all. (p. 345)

Speaking to each other, the historians refer to the Shackleton expedition several times, and they are apparently as marooned as the Antarctic explorers were, although they are not as literally alone.

One of the highlights of the book is Polly’s relationship with Sir Godfrey, a Shakespearean actor many years her senior. It’s a beautiful story within the story, which makes the historians’ self-containment in the first half of the book all the more aggravating.

The ending resolves the question that has haunted both novels, and wraps up the characters’ personal stories, although not without cost to nearly all of them. Willis understates many of the final developments, letting readers figure out events and connections themselves. It’s a lovely ending, I just wish the journey there had been less tiresome.